The Earth’s magnetic field, a silent, invisible shield, has long been understood to be a fundamental aspect of our planet’s environment. It extends far beyond the atmosphere, forming a protective bubble known as the magnetosphere, which deflects the harsh stream of charged particles emanating from the Sun – the solar wind. This magnetic field is not static; it is a dynamic entity, constantly in flux. Among its most profound and intriguing changes is the phenomenon of magnetic pole reversal, a process that has occurred repeatedly throughout Earth’s history. Understanding this shift allows for a deeper appreciation of our planet’s internal processes and its vulnerability to external forces.

The Earth’s magnetic field is not generated by a giant bar magnet embedded within the planet, as a common analogy might suggest. Instead, it originates from a complex and energetic process occurring deep within the Earth’s core. This process, known as the geomagnetic dynamo, is the engine that powers our planet’s magnetic shield.

The Liquid Outer Core: A Molten Metal Sea

Beneath the solid inner core lies the outer core, a vast ocean of molten iron and nickel. This molten metal is not at rest; it is in constant, turbulent motion, driven by a combination of heat escaping from the inner core and the Earth’s rotation. Imagine this outer core as a colossal, churning, metallic soup.

Convective Currents: The Stirring of the Cauldron

The primary driver of this motion is convection. Heat from the cooling inner core creates regions of less dense, hotter metal that rise, while cooler, denser metal sinks. This creates vast, swirling currents, much like the currents in a pot of boiling water, but on a planetary scale and composed of electrically conductive fluid.

Coriolis Effect: The Swirls Take Shape

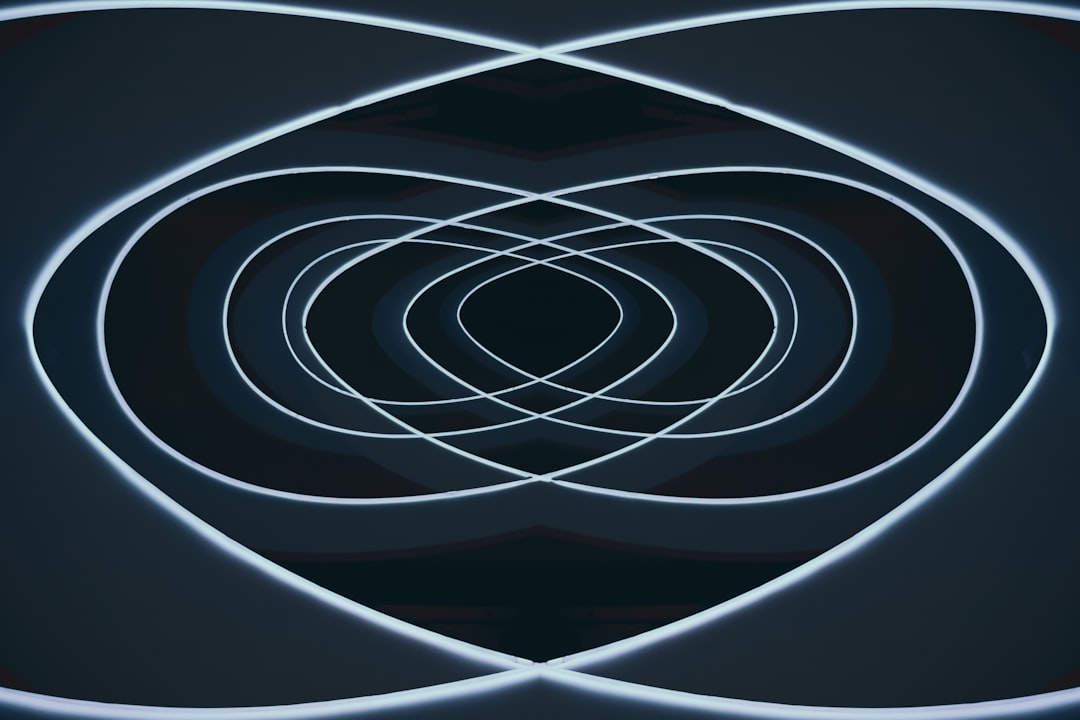

The Earth’s rotation plays a crucial role in shaping these convective currents. The Coriolis effect deflects moving fluids, causing them to spiral. In the outer core, this effect organizes the chaotic convection into helical patterns, akin to long, spiraling columns of fluid. It is these organized, spiraling flows of conductive material that generate electrical currents.

Electromagnetism at Play: The Birth of the Field

According to the principles of electromagnetism, any moving electrical charge creates a magnetic field. The vast, organized electrical currents flowing within the molten outer core generate the Earth’s dipolar magnetic field. This field, with its north and south magnetic poles, is a direct consequence of the dynamic ballet of molten metal deep underground. Think of it as a giant, self-sustaining electrical generator, where the motion of the fluid metal acts as the rotor and the magnetic field it generates, in turn, influences the motion, creating a feedback loop.

Magnetic pole reversals are fascinating geological events that have occurred throughout Earth’s history, significantly impacting the planet’s magnetic field and environment. For a deeper understanding of what these reversals entail and their potential effects on life and technology, you can explore a related article on this topic. This article provides insights into the mechanisms behind magnetic pole reversals and their implications for our modern world. To read more, visit Freaky Science.

Tracking the Shifting Poles: Paleomagnetism as Earth’s Magnetic Compass

The evidence for past magnetic pole reversals is not retrieved from a magical celestial compass but from the rocks themselves. This field of study, known as paleomagnetism, allows scientists to peer into Earth’s ancient magnetic past.

Magnetic Minerals: Tiny Recorders of Field Direction

Many rocks, particularly those of volcanic origin, contain tiny magnetic minerals, such as magnetite. When lava cools and solidifies, these magnetic minerals align themselves with the Earth’s magnetic field at that precise moment in time. They become like microscopic compass needles, forever frozen in their orientation.

Lava Flows: Snapshot in Time

Each lava flow, from a volcanic eruption, represents a snapshot of the Earth’s magnetic field at the time the lava cooled. As these lavas solidify, they trap the direction and intensity of the magnetic field like a geological photograph.

Sedimentary Rocks: A Slower Deposition

In sedimentary rocks, which form from the accumulation of eroded particles that eventually settle and lithify, the magnetic grains within them also align with the Earth’s magnetic field as they are deposited. This process is slower than in lava flows, but it still captures a record of the prevailing magnetic conditions.

The Magnetic Striping of the Seafloor: A Convincing Record

One of the most compelling pieces of evidence for magnetic reversals comes from the ocean floor. As new oceanic crust is formed at mid-ocean ridges, it records the Earth’s magnetic field.

Seafloor Spreading: A Conveyor Belt of Magnetism

At mid-ocean ridges, magma rises from the mantle, cools, and solidifies to form new oceanic crust. This process of seafloor spreading is like a geological conveyor belt, continuously moving this newly formed crust away from the ridge. As the crust forms and cools, it records the magnetic polarity of the Earth at that time.

Symmetrical Patterns: A Mirror Image of History

As the Earth’s magnetic field periodically reverses, new sections of crust form with the opposite magnetic polarity. This results in striking symmetrical patterns of magnetic stripes on either side of the mid-ocean ridges. These stripes, alternating between normal and reversed polarity, are like a bar code of Earth’s magnetic history, providing irrefutable evidence of past reversals.

Dating the Reversals: Building a Timeline of Change

By using radiometric dating techniques on volcanic rocks associated with these magnetic anomalies, scientists can determine the age of these magnetic reversals, constructing a timeline of changes in Earth’s magnetic field. This allows us to pinpoint when the magnetic poles have swapped.

The Process of Reversal: A Messy, Gradual Transition

Contrary to a sudden flip-flop, a magnetic pole reversal is not an instantaneous event. It is a complex and prolonged process that can take thousands of years to complete, during which the Earth’s magnetic field undergoes significant weakening and reorganization.

Weakening of the Field: A Fraying Shield

As a reversal approaches, the strength of the Earth’s magnetic field begins to decrease. This weakening is not uniform across the globe; it is often characterized by the emergence of multiple magnetic poles or the development of complex, multipolar field configurations. Imagine the magnetic shield becoming less like a solid, robust barrier and more like a tattered, permeable fabric.

Multiple Poles: A Chaotic Landscape

During the reversal process, the familiar dipole field can break down, leading to the appearance of several north and south magnetic poles scattered across the globe. This creates a highly unpredictable and chaotic magnetic landscape.

Intensity Fluctuations: A Rollercoaster Ride

The intensity of the magnetic field can also fluctuate dramatically during a reversal, waxing and waning in strength. This period of instability is a hallmark of the transition.

The Wander of the Magnetic Poles: A Shifting Compass

The geographic locations of the magnetic north and south poles are not fixed. They are known to wander over time, and during a reversal, this wandering can become particularly pronounced. The poles may move erratically and at accelerated speeds before settling into their new, reversed positions.

Geomagnetic Excursions: Brief Deviations

Within the larger reversal process, there can be instances of geomagnetic excursions, where the magnetic field briefly deviates significantly from its overall dipole structure before returning to its original polarity. These excursions are like temporary detours on the road to a full reversal.

Re-establishment of the Dipole: A New Orientation

Once the most chaotic phase has passed, the magnetic field begins to re-establish itself as a dipole, but with the polarity inverted. The magnetic north pole becomes the magnetic south pole, and vice versa. This new dipole field will then continue to evolve over geological timescales.

Implications of a Reversal: Challenges and Adaptations

While the Earth has undergone countless magnetic pole reversals throughout its history without an extinction-level event directly attributable to them, such shifts still hold significant implications for life on Earth and our technological infrastructure.

Increased Radiation Exposure: A Thinner Shield

The primary concern during a magnetic pole reversal is the significant weakening of the Earth’s magnetic field, which acts as a primary defense against harmful cosmic rays and solar energetic particles. With a diminished magnetic shield, the surface of the Earth would be exposed to higher levels of radiation.

Cosmic Rays: High-Energy Visitors

Cosmic rays are high-energy particles originating from outside our solar system. While the magnetosphere deflects most of these, a weaker field would allow more of them to reach the Earth’s surface.

Solar Flares and Coronal Mass Ejections: The Sun’s Outbursts

The Sun, a star of immense power, periodically releases bursts of charged particles in the form of solar flares and coronal mass ejections. The magnetosphere is our primary defense against these events, and a weakened field would make us more vulnerable to their potentially disruptive effects.

Impact on Navigation: Lost in the Magnetic Maze

For millennia, humans and animals have relied on the Earth’s magnetic field for navigation. During a reversal, the erratic behavior of the magnetic poles would render traditional magnetic compasses unreliable.

Animal Migration: A Disrupted Inner Compass

Many migratory animals, such as birds and whales, use the Earth’s magnetic field as an internal compass to guide their long journeys. A chaotic magnetic field could severely disrupt these migration patterns.

Human Navigation: A Return to the Stars

Humankind’s reliance on magnetic navigation would necessitate a shift towards alternative methods, such as celestial navigation or the development of new, robust positioning technologies.

Technological Vulnerabilities: The Grid Under Threat

Our increasingly interconnected world relies heavily on electronic infrastructure, which can be susceptible to disruptions from geomagnetic storms.

Satellites: The First Line of Defense Under Siege

Satellites in orbit are particularly vulnerable to increased radiation and charged particle bombardment. A weakened magnetic field would increase the risk of satellite damage or malfunction, impacting communication, GPS, and weather monitoring systems.

Power Grids: The Risk of Induction

Geomagnetic storms can induce powerful currents in long conductors, such as power lines. During a pole reversal, with a weaker and more complex magnetic field, the risk of induced currents damaging power grids could be amplified, potentially leading to widespread blackouts.

A magnetic pole reversal is a fascinating geological phenomenon that occurs when the Earth’s magnetic field flips, causing the magnetic north and south poles to switch places. This event can have significant effects on the planet, including changes in animal migration patterns and increased exposure to solar radiation. For a deeper understanding of what a magnetic pole reversal looks like and its potential implications, you can read more in this informative article on Freaky Science.

The Future of Our Magnetic Field: Predicting the Next Shift

| Aspect | Description | Metric / Data |

|---|---|---|

| Duration of Reversal | Time taken for the magnetic poles to completely reverse | Typically 1,000 to 10,000 years |

| Magnetic Field Strength | Intensity of Earth’s magnetic field during reversal | Can drop to 10-20% of normal strength |

| Frequency of Reversals | How often magnetic pole reversals occur | On average every 200,000 to 300,000 years |

| Transition Behavior | Pattern of magnetic field during reversal | Multiple poles can appear at different latitudes before settling |

| Impact on Navigation | Effect on animal and human navigation systems | Temporary disorientation; animals adapt over time |

| Geological Evidence | Data source for studying reversals | Magnetized minerals in volcanic and sedimentary rocks |

| Solar Radiation Exposure | Change in Earth’s protection from solar and cosmic radiation | Increased exposure due to weakened magnetic field |

The study of magnetic pole reversals is not merely an academic pursuit; it is a crucial aspect of understanding our planet’s long-term habitability and preparing for future challenges.

The Current State of the Field: A Measured Drift

Scientists continuously monitor the Earth’s magnetic field using a global network of observatories. Current observations show that the magnetic north pole is drifting at an accelerated rate, and the field itself is weakening.

The South Atlantic Anomaly: A Weak Spot

A notable feature of the current magnetic field is the South Atlantic Anomaly, a region where the magnetic field is significantly weaker than elsewhere. This anomaly is thought to be related to an ongoing process within the Earth’s core that may be a precursor to a reversal.

The Pace of Change: A Geological Clock

While the exact timing of the next pole reversal cannot be precisely predicted, geological evidence suggests that reversals occur irregularly, with periods of stability interspersed with rapid transitions. On average, reversals have occurred every few hundred thousand years, but this is a statistical average, and the actual timing varies significantly.

Estimating the Next Reversal: A Statistical Guess

Based on the historical record of reversals and the current observed weakening of the field, some scientists estimate that the next reversal could occur within the next 1,000 to 10,000 years. However, these are broad estimates, and the true timing remains uncertain.

Research and Monitoring: A Watchful Eye on Our Invisible Shield

Ongoing research into the geodynamo and continuous monitoring of the Earth’s magnetic field are essential for improving our understanding of these complex processes.

Advanced Modeling: Simulating the Dynamo

Scientists are using advanced computer models to simulate the behavior of the Earth’s core and the geomagnetic dynamo. These models help to better understand the mechanisms driving reversals and potentially refine predictions about future events.

Space-Based Observatories: A Global Perspective

Space-based missions dedicated to observing the Earth’s magnetic field provide invaluable data from a global perspective, complementing ground-based observations and offering a more comprehensive understanding of the field’s dynamics.

FAQs

What is a magnetic pole reversal?

A magnetic pole reversal is a phenomenon where the Earth’s magnetic north and south poles switch places. This means that the magnetic north pole becomes the magnetic south pole and vice versa.

How often do magnetic pole reversals occur?

Magnetic pole reversals happen irregularly, approximately every 200,000 to 300,000 years on average. However, the timing is not consistent, and the last reversal occurred about 780,000 years ago.

What does a magnetic pole reversal look like?

During a magnetic pole reversal, the Earth’s magnetic field weakens and becomes more complex, with multiple magnetic poles appearing at different locations. This process can take thousands of years and is not a sudden flip.

Can a magnetic pole reversal affect life on Earth?

While a magnetic pole reversal can weaken the Earth’s magnetic field temporarily, which may increase exposure to solar and cosmic radiation, there is no evidence that it causes mass extinctions or catastrophic effects on life.

How do scientists study magnetic pole reversals?

Scientists study magnetic pole reversals by examining the magnetic properties of ancient rocks and sediments, which record the direction and intensity of Earth’s magnetic field at the time they were formed. This helps reconstruct the history of past reversals.