The origin and development of the human brain, a complex organ responsible for our unique cognitive abilities, has been a subject of intense scientific inquiry. Among the many theories proposed, the “Evolutionary Big Brain First Theory” posits that significant encephalization – the increase in brain size relative to body size – was a primary driver, rather than a subsequent adaptation, in the trajectory of human evolution. This perspective challenges earlier models that often placed the development of upright posture, tool use, or language as initial catalysts, suggesting instead that a larger brain provided the adaptive advantages necessary for these subsequent developments to flourish.

The “Big Brain First Theory” is not a singular, monolithic idea but rather a collection of hypotheses that coalesce around the central tenet of early encephalization. Its proponents argue that the selective pressures favoring increased brain volume were present much earlier in hominin evolution than traditionally thought.

Early Hominin Encephalization

Fossil evidence provides crucial insights into the evolution of brain size.

- Australopithecus and Homo habilis: While Australopithecus species possessed brains only slightly larger than those of modern chimpanzees, the emergence of Homo habilis around 2.4 million years ago marks a significant inflection point. Their cranial capacity, averaging around 600-700 cubic centimeters (cc), represented a substantial increase compared to their australopithecine ancestors. This jump is often cited as the initial wave of encephalization, preceding widespread sophisticated tool use or complex social structures.

- Rapid Expansion in Homo Erectus: The subsequent Homo erectus, appearing around 1.9 million years ago, exhibited even greater brain enlargement, with cranial capacities ranging from 800-1200 cc. This species was geographically widespread, developed more advanced lithic technologies (Acheulean tools), and likely had more complex social behaviors, all of which could be seen as facilitated by their larger brains rather than solely driving their development.

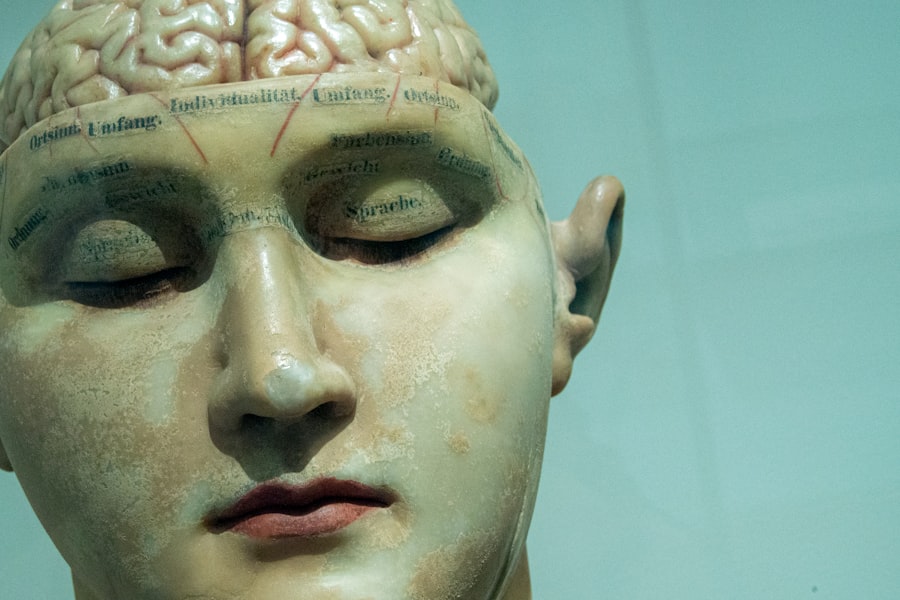

- Anatomical Correlates of Brain Growth: Studies of endocasts – natural molds of the brain found within fossil crania – reveal changes in brain organization alongside growth in size. These changes include a relative expansion of the frontal lobes, associated with planning and decision-making, and the temporal lobes, crucial for memory and language processing.

The Role of Metabolic Costs

The human brain, despite representing only about 2% of total body weight, consumes a disproportionate amount of energy—approximately 20-25% of the body’s basal metabolic rate. This significant metabolic cost presents an evolutionary puzzle.

- Nutritional Demands: Proponents of the big brain first theory suggest that early hominins must have secured a consistently rich and reliable food source to sustain such an metabolically expensive organ. This could have involved scavenging, increased meat consumption, or exploiting diverse ecological niches.

- Trade-offs and Synergies: The metabolic burden of a large brain necessitated trade-offs in other physiological systems. For instance, some theories propose a “gut-brain trade-off,” where a reduction in gut size (due to a high-quality, easily digestible diet) freed up energy for brain development. The ability of a larger brain to then locate and process these high-quality foods could have created a positive feedback loop, driving further encephalization.

The evolutionary big brain first theory posits that the development of larger brains in humans was a primary driver of our species’ success, influencing social structures, problem-solving abilities, and communication skills. For a deeper exploration of this concept and its implications on human evolution, you can read the related article found at Freaky Science. This article delves into the various factors that contributed to brain expansion and how they shaped our ancestors’ survival and adaptation strategies.

Environmental and Social Catalysts for Early Brain Growth

While the “Big Brain First Theory” emphasizes early encephalization, it does not disregard the influence of environmental and social factors. Instead, it posits that these factors acted as powerful selective pressures favoring individuals with larger, more capable brains.

Climatic Instability and Adaptability

The Pliocene and Pleistocene epochs, periods characterized by significant climatic fluctuations, offered a dynamic backdrop for human evolution.

- Cognitive Flexibility for Survival: Changing environments, shifting resource availability, and novel challenges would have favored individuals with enhanced cognitive abilities – problem-solving skills, memory for spatial layouts and resource locations, and the capacity to adapt to new situations. A larger brain, therefore, presented an invaluable “Swiss Army knife” in an uncertain world.

- Expanding Dietary Niches: As environments changed, traditional food sources might have become scarce, forcing hominins to exploit new dietary niches. A larger brain could have facilitated the identification of new edible plants, the development of strategies for hunting new prey, or the processing of tougher or less palatable foods.

Social Complexity and Cooperation

The benefits of social living in early hominin groups would also have exerted selection pressure for enhanced cognitive abilities.

- Theory of Mind and Empathy: Navigating complex social hierarchies, forming alliances, understanding intentions, and cooperating in tasks like hunting or child-rearing require sophisticated cognitive functions often associated with larger brains. The ability to anticipate the actions of others (a rudimentary “theory of mind”) would have conferred a significant advantage.

- Communication and Group Cohesion: While symbolic language as we know it likely emerged much later, proto-language or more sophisticated forms of non-verbal communication would have been crucial for group coordination and information sharing. A larger brain could have provided the neural architecture for improved communication skills, fostering stronger group bonds and more effective collective action.

Consequences of Early Encephalization

The “Big Brain First Theory” suggests that a larger brain wasn’t just a passive recipient of evolutionary pressures, but an active agent, shaping subsequent evolutionary trends.

Tool Technology and Innovation

The burgeoning brain provided the scaffolding for increasingly sophisticated tool-making abilities.

- Oldowan to Acheulean Progression: The earliest tools, Oldowan choppers, required basic motor control and an understanding of flake production. The transition to Acheulean handaxes, however, demanded more abstract planning, symmetrical fabrication, and a longer sequence of operational steps – skills greatly enhanced by a larger, more organized brain.

- Cognition in Tool Use: Beyond mere dexterity, tool use required an understanding of material properties, cause-and-effect relationships, and the ability to imagine the finished product from a raw stone. These cognitive demands likely drove further brain development through a feedback loop.

Language and Symbolic Thought

Though the exact timing remains debated, the development of complex language and symbolic thought is strongly linked to brain size and organization.

- Neurological Substrates: Regions like Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas, critical for language production and comprehension in modern humans, show evolutionary antecedents in the brains of early Homo species, as inferred from endocasts.

- Cognitive Precursors: A larger brain would have provided the necessary cognitive capacity for the abstract thought, categorization, memory, and sequential processing fundamental to language acquisition and symbolic reasoning. The ability to conceptualize, categorize, and assign arbitrary meanings to sounds and gestures is a hallmark of human intelligence, and it is difficult to imagine its emergence without a powerful brain to support it.

Challenges and Rebuttals to the Theory

Like any scientific hypothesis, the “Big Brain First Theory” faces scrutiny and alternative interpretations.

The “Body First” or “Bipedalism First” Arguments

Some theories prioritize other evolutionary milestones as the initial drivers of hominin success.

- Bipedalism as the Prime Mover: The “Bipedalism First” hypothesis posits that upright posture freed the hands, allowing for tool manipulation and carrying, which then indirectly led to brain expansion. Fossil evidence for early bipedalism, such as Ardipithecus ramidus and Australopithecus afarensis, predates significant encephalization. The “Big Brain First” proponents would counter that while bipedalism offered distinct advantages for locomotion and resource acquisition, ultimately, it was the integration with a more capable brain that truly unleashed its potential. Being upright might have been a useful chassis, but a more powerful engine was needed to truly take off.

- Tool Use as an Initial Catalyst: Another perspective suggests that the demands of tool-making and use were the primary drivers of brain growth. The circularity of this argument is often highlighted: did a smarter brain make tools, or did tools make the brain smarter? The “Big Brain First” perspective suggests the former, arguing that a baseline level of cognitive capability, supported by an already larger brain, was necessary to initiate and refine habitual tool use.

The Problem of Defining “Big First”

The term “Big First” itself can be ambiguous.

- Relative vs. Absolute Size: It is important to distinguish between absolute brain size and relative brain size (encephalization quotient, EQ). While absolute brain size increased, the question remains at what point this increase became the primary driver rather than a co-evolutionary trait. The theory generally refers to significant relative encephalization preceding other complex behaviors.

- Thresholds of Brain Function: There is also the question of whether there was a particular threshold of brain size or organization that was critical for unlocking advanced cognitive abilities. Small increases might not have been enough; a substantial leap might have been required to tip the scales.

The evolutionary big brain first theory suggests that the development of larger brains in humans was a primary driver of our species’ success, influencing everything from social structures to technological advancements. A related article that delves deeper into the implications of this theory can be found on Freaky Science, where it explores how cognitive evolution has shaped human behavior and culture. For more insights, you can read the article here.

Future Directions and Continued Research

| Metric | Description | Value / Data | Source / Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brain Size Increase | Average increase in hominin brain volume over 2 million years | From ~400 cm³ to ~1350 cm³ | Falk, 2014; Aiello & Wheeler, 1995 |

| Timeframe of Brain Expansion | Period during which significant brain enlargement occurred | 2 million to 200,000 years ago | DeSilva & Lesnik, 2006 |

| First Big Brain Species | Earliest hominin species with significantly larger brain size | Homo habilis (~600-700 cm³) | Leakey et al., 1964 |

| Correlation with Tool Use | Relationship between brain size and complexity of tools | Positive correlation; more complex tools with larger brains | Stout et al., 2008 |

| Metabolic Cost of Big Brain | Percentage of basal metabolic rate used by the brain | Up to 20% in modern humans | Aiello & Wheeler, 1995 |

| Evolutionary Advantage | Hypothesized benefits of larger brain size | Improved problem solving, social interaction, and survival | Reader & Laland, 2002 |

The “Evolutionary Big Brain First Theory” continues to be a vibrant area of research, fueled by new fossil discoveries, advancements in neuroimaging, and sophisticated computational models.

Integrating Multiple Lines of Evidence

Future research will likely continue to synthesize data from diverse fields.

- Paleoanthropology and Archaeology: New fossil finds, particularly those with well-preserved cranial remains, can provide further clarity on brain size evolution. Archaeological sites offer direct evidence of tool technology, dietary shifts, and social behaviors, allowing for better correlation with brain development.

- Genetics and Neuroscience: Comparative genomics can shed light on the genetic underpinnings of human brain development, including genes associated with brain size and cognitive function. Neuroscientific studies of primate brains offer insights into the functional implications of brain organization and growth. Understanding the genetic “instructions” that led to a larger brain is crucial.

- Computational Modeling: Advanced computational models can simulate the interactions between environmental pressures, brain development, and behavioral outcomes, helping to test the robustness of the “Big Brain First Theory” and its alternatives.

Refinements to the Theory

The “Big Brain First Theory” is not a static concept but one that will continue to be refined as new evidence emerges.

- Nuanced Causal Pathways: Future iterations of the theory may explore more nuanced causal pathways, acknowledging that while a large brain may have been a primary driver, it interacted with and was shaped by other factors in a complex, co-evolutionary dance. It’s less a single domino fall and more a complex, intertwined web of cause and effect.

- Regional Brain Development: Instead of focusing solely on overall brain size, future research may delve deeper into the evolution of specific brain regions and their connectivity, seeking to understand how changes in particular areas, such as the prefrontal cortex, might have conferred specific selective advantages.

In conclusion, the “Evolutionary Big Brain First Theory” presents a compelling argument for the early and influential role of encephalization in human evolution. It posits that the development of a larger, more capable brain provided the cognitive foundation upon which many uniquely human traits – sophisticated tool use, complex language, and intricate social structures – were built. While acknowledging the importance of other evolutionary adaptations, this perspective places the brain at the forefront, not merely as a consequence, but as a proactive architect of the human lineage. As the scientific understanding of our past continues to unfold, this theory will undoubtedly remain a central pillar in the ongoing quest to comprehend the remarkable journey of the human mind.

FAQs

What is the evolutionary big brain first theory?

The evolutionary big brain first theory suggests that the development of a larger brain was one of the earliest and most significant evolutionary changes in human ancestors. This theory posits that an increase in brain size preceded other major evolutionary adaptations, such as changes in body structure or tool use.

How does the big brain first theory differ from other evolutionary theories?

Unlike theories that emphasize physical adaptations like bipedalism or tool-making as primary drivers of human evolution, the big brain first theory argues that brain enlargement was the initial and most critical evolutionary step. It highlights cognitive development as the foundation for subsequent evolutionary changes.

What evidence supports the evolutionary big brain first theory?

Fossil records showing early hominins with relatively large brain sizes compared to their body size support this theory. Additionally, archaeological findings of early complex behaviors and tool use correlate with increased brain capacity, suggesting cognitive advancements occurred early in human evolution.

What are the implications of the big brain first theory for understanding human evolution?

If brain enlargement was the first major evolutionary change, it implies that cognitive abilities such as problem-solving, social interaction, and communication were crucial for survival and adaptation. This perspective shifts the focus to mental capabilities as the driving force behind human evolution.

Are there any criticisms or limitations of the evolutionary big brain first theory?

Some scientists argue that brain size alone does not fully explain human evolution, emphasizing the importance of other factors like environmental changes, social structures, and physical adaptations. Additionally, brain efficiency and organization may be as important as size, which the theory may not fully address.