On September 1, 1859, the Earth experienced a celestial event of unparalleled magnitude in recorded history: the Carrington Event. This solar storm, a violent eruption from the Sun’s surface, unleashed a torrent of energized particles and magnetic fields towards our planet, profoundly impacting nascent technological infrastructures and captivating observers with dazzling atmospheric displays. While a distant historical footnote to many, the Carrington Event serves as a stark reminder of Earth’s vulnerability to solar activity and a potent case study for understanding potential future threats.

To comprehend the Carrington Event, one must first grasp the fundamental dynamics of our star, the Sun. Far from a placid orb, the Sun is a dynamic, turbulent sphere of superheated plasma, a powerhouse of nuclear fusion constantly churning and erupting. Its surface, the photosphere, is dotted with sunspots – cooler, darker regions where intense magnetic fields become concentrated. These magnetic fields, like twisted rubber bands, can store enormous amounts of energy. You can learn more about the earth’s magnetic field and its effects on our planet.

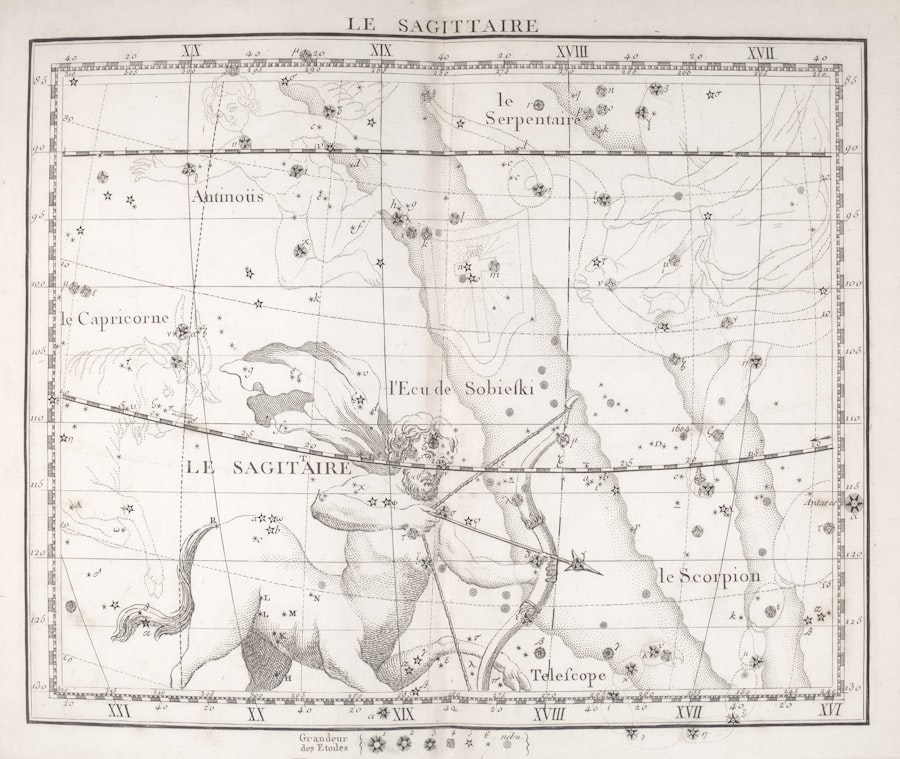

Sunspots and Magnetic Activity

Sunspots are key indicators of solar activity. Their number and distribution follow an approximately 11-year cycle, waxing and waning in intensity. During periods of high solar activity, the sunspot count increases, and with it, the likelihood of powerful solar flares and coronal mass ejections (CMEs). The Carrington Event occurred during a period of particularly intense solar activity, demonstrating the direct link between sunspot activity and solar storm severity. Imagine these sunspots as the eye of an approaching storm; their presence signals brewing disturbances.

Solar Flares: The Flash of Light

A solar flare is a sudden, intense burst of radiation from the Sun’s surface, often originating near sunspot groups. These flares release energy across the electromagnetic spectrum, from radio waves to X-rays and gamma rays, at speeds that defy human comprehension. The August 28, 1859, a significant precursor to the Carrington Event, was observed as an exceptionally bright flare, marking the initial discharge of energy. Think of a solar flare as the lightning strike that announces the storm’s arrival, a brilliant, instantaneous burst of light.

Coronal Mass Ejections (CMEs): The Expulsion of Plasma

While solar flares are dramatic, it is the coronal mass ejection (CME) that poses the greatest threat to Earth. A CME is a massive expulsion of plasma and magnetic field from the Sun’s outer atmosphere, the corona, into interplanetary space. These colossal bubbles of charged particles can travel at speeds ranging from a few hundred to thousands of kilometers per second. If a CME is directed towards Earth, its impact can trigger geomagnetic storms, like the Carrington Event. Consider a CME as the tidal wave following the lightning strike, a massive, slower-moving but incredibly powerful force that travels across the ocean of space.

The Carrington Event of 1859, one of the most powerful solar storms recorded in history, serves as a stark reminder of the potential impact of solar activity on modern technology. For those interested in exploring the implications of such solar events, a related article can be found at Freaky Science, which delves into the science behind solar storms and their effects on Earth. Understanding these phenomena is crucial as we continue to rely heavily on technology that could be vulnerable to similar events in the future.

The Observation and Impact: A Global Spectacle and Technological Disruption

The Carrington Event did not arrive unannounced. Its effects began with an unprecedented display of auroras and culminated in widespread technological disruptions, offering a glimpse into a world grappling with a new, invisible force.

Richard Carrington’s Groundbreaking Observation

On September 1, 1859, British astronomer Richard Carrington was meticulously sketching sunspots when he witnessed an extraordinary phenomenon. Two intensely bright spots of white light erupted within a large sunspot group. This “white-light flare” was exceptionally rare and marked the direct observation of the solar flare believed to have triggered the Carrington Event CME. This observation was pivotal, as it provided the first direct evidence linking a specific solar event to subsequent geomagnetic activity on Earth. Carrington, a keen observer, essentially identified the fuse that ignited the global phenomenon.

The Aurora Borealis and Australis: A Sky Ablaze

The most visually striking consequence of the Carrington Event was the spectacular and widespread auroral displays. Normally confined to polar regions, the auroras were seen across vast swathes of the globe, from the Caribbean to Queensland, Australia. Gold miners in the Rocky Mountains woke up at 1 a.m., thinking it was dawn, and began preparing breakfast. Newspapers reported skies “ablaze” with crimson and emerald hues, inspiring awe and, in some cases, trepidation. Imagine the sky transformed into a canvas of shifting, vibrant colors, an ethereal light show unfurling far from its usual polar confines. These were not merely pretty lights; they were the visible manifestations of Earth’s magnetic field being buffeted by the solar storm.

Telegraph Systems: The First Casualties

The fledgling global telegraph network bore the brunt of the Carrington Event’s technological impacts. As the CME collided with Earth’s magnetosphere, it induced massive electrical currents within the long metallic cables of telegraph lines. These “geomagnetically induced currents” (GICs) were so powerful that they overloaded equipment, melting wires, causing sparks to fly from telegraph keys, and even setting telegraph papers on fire. Operators reported receiving shocks, and some discovered that they could operate their telegraphs even after disconnecting their batteries, using only the induced currents. This unprecedented disruption served as a sobering testament to the vulnerability of interconnected electrical systems to solar phenomena. The telegraph system, then the internet of its day, demonstrated its fragility.

Magnetic Disturbance: The Compass Goes Wild

Beyond the visible auroras and damaged telegraphs, the Earth’s magnetic field experienced profound disturbances. Geomagnetic observatories, still a relatively new scientific endeavor, recorded unprecedented fluctuations in magnetic needle readings. These disturbances impacted navigation, though the full implications for shipping and exploration were not as widely documented as the telegraph failures due to the limitations of communication and the absence of ubiquitous, sensitive navigational technology. Think of Earth’s magnetic shield as a drum, and the CME as a powerful blow, causing the drum’s surface to vibrate wildly.

Geomagnetic Storms: Understanding the Mechanism

The Carrington Event was a prime example of a severe geomagnetic storm. Understanding how these storms develop and interact with Earth’s environment is crucial for mitigating future risks.

The Earth’s Magnetosphere: Our Planetary Shield

Earth possesses a powerful magnetic field, generated by the convective motion of molten iron in its outer core. This field extends far into space, forming a protective bubble called the magnetosphere, which deflects most of the solar wind’s charged particles. Without this shield, our atmosphere would likely have been stripped away by solar radiation over billions of years, just as Mars’s atmosphere was. The magnetosphere acts as our first line of defense, a cosmic umbrella against the Sun’s energetic outbursts.

Interaction with a Coronal Mass Ejection

When a CME, laden with its own magnetic field, collides with the Earth’s magnetosphere, a complex interaction occurs. If the CME’s magnetic field is oriented southward, it directly opposes Earth’s northward-pointing field, causing the two fields to “reconnect.” This reconnection process allows solar wind particles to funnel into the polar regions, exciting atmospheric gases and producing the spectacular auroras. More importantly, it transfers immense energy into the magnetosphere, driving potent electrical currents. This is when the cosmic umbrella begins to buckle under the force of the solar wind.

Geomagnetically Induced Currents (GICs)

The sudden, intense fluctuations in Earth’s magnetic field during a geomagnetic storm induce powerful electrical currents in long conductors on the surface, such as power grids, pipelines, and telegraph lines. These are the GICs that devastated the 1859 telegraph network. Modern power grids, with their vast interconnectedness and reliance on transformers, are particularly susceptible. GICs can saturate transformers, causing them to overheat and fail, leading to widespread power outages. This phenomenon is why the Carrington Event is not merely a historical curiosity but a real-world threat to contemporary society.

Modern Vulnerabilities: A World Transformed

While the 1859 world was significantly less technologically dependent than today’s, a repeat of the Carrington Event in the 21st century would have far more devastating and widespread consequences. Our interconnected, electronic civilization is inherently fragile in the face of such a cosmic onslaught.

Power Grids: The Achilles’ Heel

The most significant vulnerability today lies in our global power grids. The high-voltage transmission lines, particularly those traversing high latitudes, are exceptionally susceptible to GICs. A sufficiently powerful geomagnetic storm could induce currents that overload and permanently damage hundreds, even thousands, of high-voltage transformers simultaneously. Replacing these massive, specialized units is a time-consuming and expensive process, potentially leading to widespread, long-duration power outages lasting for weeks, months, or even years in some regions. Imagine entire continents plunged into darkness, not for hours, but for extended periods.

Satellite Infrastructure: Eyes and Ears in Space

Modern society relies heavily on satellites for communication, navigation (GPS), weather forecasting, and defense. A severe solar storm could directly damage or disable these satellites through radiation exposure or by inducing destructive currents. The loss of GPS alone would cripple countless industries, from transportation and logistics to precise timing for financial transactions. Furthermore, disruption to communication satellites would sever vital links across the globe. Our orbital infrastructure, the eyes and ears of our modern world, is particularly exposed.

Aviation and Navigation: A Blind Flight

While pilots are trained for instrument failure, an extreme solar storm could disrupt critical navigation systems, communications, and even expose flight crews and passengers to elevated radiation levels, particularly on high-latitude routes. Commercial aircraft rely heavily on GPS and satellite communication, both of which would be profoundly impacted. Ships at sea, relying on satellite navigation, would also face significant challenges. The sophisticated systems that guide our journeys could essentially become unreliable or even inoperable.

Telecommunications and the Internet: The Global Network Unplugged

Beyond power grids, the physical infrastructure of the internet – particularly long-haul fiber optic cables that rely on repeaters powered by ground-based stations – could be vulnerable to GICs. While fiber optics themselves are immune to GICs, the electronics that drive them are not. Disruption to the power grid would inevitably lead to a massive outage of internet services, further isolating communities and hindering emergency response efforts. The global nervous system, our internet, could be severely compromised.

The Carrington Event of 1859 remains one of the most significant solar storms in recorded history, showcasing the potential impact of solar activity on Earth. For those interested in exploring the implications of such solar events on modern technology and infrastructure, a related article can provide valuable insights. You can read more about this topic in the article on solar storms and their effects on our daily lives by visiting this link. Understanding these phenomena is crucial as we continue to rely heavily on technology that could be vulnerable to similar solar events in the future.

The Future: Mitigation and Resilience

| Metric | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Date | September 1-2, 1859 | Dates when the Carrington Event occurred |

| Solar Flare Class | X45 (estimated) | Estimated intensity of the solar flare associated with the event |

| Geomagnetic Storm Intensity | Dst index approx. -850 nT | Estimated disturbance storm time index indicating storm strength |

| Duration of Auroras | Several days | Length of time auroras were visible at low latitudes |

| Latitude of Auroras | As low as 20° N | Lowest latitude where auroras were observed |

| Telegraph System Impact | Widespread disruptions and fires | Effect on telegraph systems including outages and equipment damage |

| Estimated CME Speed | ~2,500 km/s | Speed of the coronal mass ejection that caused the storm |

The Carrington Event serves as a powerful historical analogue, driving contemporary scientific research and policy discussions aimed at preparing for future solar storms. While we cannot prevent these cosmic events, we can certainly build resilience.

Space Weather Monitoring: The Early Warning System

Advanced space weather observatories, both ground-based and space-based, are continuously monitoring the Sun for eruptions. Satellites like SOHO and STEREO provide crucial data on solar flares and CMEs, giving forecasters some lead time – typically hours to a few days – to issue warnings. This early warning system is akin to a meteorological radar for space, providing crucial minutes or hours to prepare.

Grid Hardening and Preparedness

Efforts are underway to “harden” power grids against GICs. This includes installing transformers with enhanced resistance to saturation, implementing operational procedures to reduce grid load during alerts, and developing more sophisticated protective relays. Utilities are also stockpiling spare transformers, recognizing the immense lead time required for their manufacture and delivery. National and international exercises simulating severe space weather events are also being conducted to test response protocols and identify weaknesses.

International Cooperation and Research

Understanding and preparing for space weather requires a global effort. Scientists and policymakers from around the world are collaborating to share data, advance research, and develop international standards for preparedness. This collaborative approach recognizes that a severe solar storm is a global threat, transcending national borders. The Sun’s fury knows no political boundaries, and our defense must be equally comprehensive.

Public Awareness and Education

Finally, educating the public about the risks of space weather is crucial. Just as we prepare for terrestrial storms, understanding the potential impacts of solar storms allows for informed decision-making and fosters greater community resilience. Knowing that a solar storm could cause a power outage for weeks is not meant to incite panic, but to empower individuals and communities to prepare wisely.

The Carrington Event, though a distant echo from the past, remains a vivid and vital lesson. It forces us to acknowledge our place in a larger cosmos, subject to forces far beyond our control. By understanding its mechanisms, preparing our infrastructure, and fostering global collaboration, humanity can strive to weather the next great solar storm, much like a seasoned sailor bracing for a tempest on a vast, unpredictable ocean. The question is not if another Carrington-level event will occur, but when. Our readiness will define its legacy.

WATCH THIS! 🌍 EARTH’S MAGNETIC FIELD IS WEAKENING

FAQs

What was the Carrington Event of 1859?

The Carrington Event was a massive solar storm that occurred in September 1859. It is considered the most powerful geomagnetic storm on record, caused by a massive coronal mass ejection (CME) from the Sun hitting Earth’s magnetosphere.

Who was Richard Carrington?

Richard Carrington was a British astronomer who observed and documented the solar flare associated with the 1859 solar storm. His detailed observations helped scientists understand the connection between solar activity and geomagnetic disturbances on Earth.

What were the effects of the Carrington Event?

The Carrington Event caused widespread auroras visible as far south as the Caribbean, disrupted telegraph systems across Europe and North America, and even caused some telegraph operators to receive electric shocks. It demonstrated the potential impact of solar storms on technology.

How long did the Carrington Event last?

The solar flare was observed on September 1, 1859, and the resulting geomagnetic storm impacted Earth over the following 1 to 2 days, with the most intense effects occurring on September 2 and 3.

Could a similar event happen today?

Yes, a similar or even stronger solar storm could occur today. Such an event could severely disrupt modern electrical grids, satellite communications, GPS systems, and other technologies that rely on electronics and space-based infrastructure.

How do scientists monitor solar storms now?

Scientists use satellites equipped with instruments to monitor solar activity, including solar flares and CMEs. Agencies like NASA and NOAA track space weather in real-time to provide warnings and forecasts to help mitigate the impact of solar storms.

What is a coronal mass ejection (CME)?

A coronal mass ejection is a large expulsion of plasma and magnetic field from the Sun’s corona. When directed toward Earth, CMEs can interact with the planet’s magnetic field, causing geomagnetic storms like the Carrington Event.

What lessons were learned from the Carrington Event?

The Carrington Event highlighted the vulnerability of electrical and communication systems to solar activity. It led to increased scientific interest in space weather and the development of monitoring systems to better predict and prepare for future solar storms.