You likely take your memories for granted, yet the process by which your brain forms, stores, and retrieves them is far more intricate and dynamic than you might imagine. Rather than simply pulling up a perfectly preserved file, your brain actively reconstructs your past experiences each time you access them. This reconstructive nature of memory is a fundamental aspect of human cognition, influencing everything from daily tasks to your sense of self.

Before you can reconstruct a memory, you must first encode it. This initial process involves transforming sensory information into a usable form for storage in your brain. Think of it as carefully laying the foundation for a complex building. You can learn more about split brain consciousness by watching this insightful video.

Sensory Input and Initial Processing

Every moment, your senses are bombarded with a vast amount of information. When you see a new face, hear a song, or touch a textured surface, this raw sensory data is first processed by specialized areas in your brain. Visual cortices handle sights, auditory cortices process sounds, and so on. This initial stage is fleeting; much of this information is quickly discarded unless it is deemed significant enough for further processing.

The Role of Attention and Emotion

Your attention acts as a filter, determining which sensory inputs are prioritized for encoding. If you’re intensely focused on a lecture, you’re more likely to encode the information presented. Conversely, distractions can lead to “encoding failures,” making it difficult to recall details later. Emotion also plays a critical role. Events tinged with strong emotions—joy, fear, surprise—are often encoded more vigorously and are consequently more vividly recalled. This is due to the involvement of structures like the amygdala, which enhances the consolidation of emotionally charged memories.

Consolidation: Solidifying the Structure

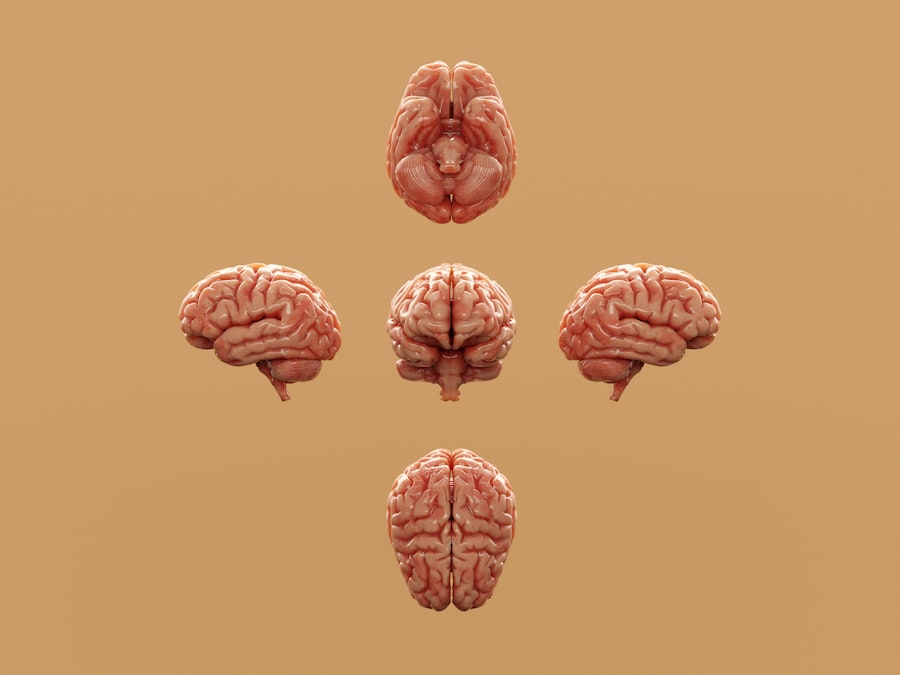

Once information has been attended to and initially processed, it undergoes a process called consolidation. This involves stabilizing the memory trace, moving it from a more fragile, temporary state to a more durable, long-term state. This process is believed to occur in stages, with the hippocampus acting as a temporary binding site, connecting various cortical regions that hold different aspects of the memory (e.g., visual details, sounds, emotions). Over time, and particularly during sleep, these connections are strengthened, and the memory becomes less dependent on the hippocampus. This is akin to the concrete in your foundation slowly hardening, making the structure more robust.

Recent studies have shed light on the intricate processes involved in how the brain reconstructs memories, revealing that our recollections are not as static as once believed. This dynamic nature of memory suggests that each time we recall an event, we may inadvertently alter the original memory, influenced by various factors such as emotions and context. For a deeper understanding of this fascinating topic, you can explore the article on memory reconstruction at Freaky Science.

Retrieval as an Act of Reconstruction: Building from Blueprints

When you recall a memory, you are not simply accessing a stored video file. Instead, your brain actively reconstructs the experience, much like an architect uses blueprints to rebuild a structure. This reconstruction is influenced by a multitude of factors, and it is rarely a perfect replica of the original event.

Cue-Dependent Retrieval

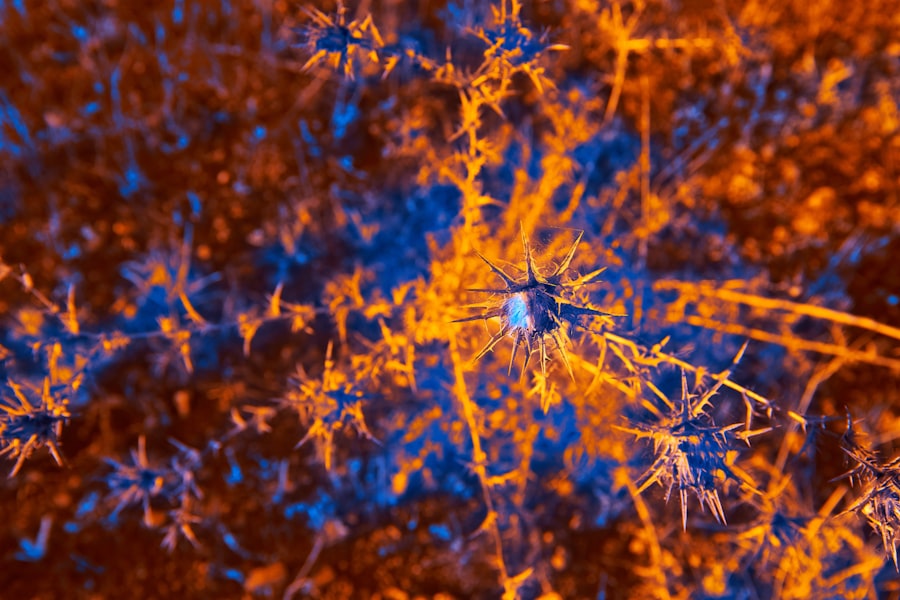

Memory retrieval is often cue-dependent. This means that specific cues, whether they are sights, sounds, smells, or even internal thoughts, can trigger the recall of a memory. When you smell a particular perfume and it instantly brings back a memory of a person, that perfume is acting as a retrieval cue. These cues activate neural networks associated with the original memory, initiating the reconstructive process.

The Role of Schemas and Scripts

Your brain utilizes schemas and scripts to fill in gaps during memory reconstruction. Schemas are generalized knowledge structures about the world – for example, your schema for a “restaurant” includes tables, chairs, waiters, menus, and food. Scripts are schemas for common sequences of events, such as “going to a doctor’s appointment.” When you recall an event, your brain leverages these pre-existing knowledge structures to fill in details that might be missing or to make the memory more coherent. If you recall attending a birthday party, your brain might automatically “add” details like cake and presents, even if you don’t specifically remember seeing them.

Source Monitoring and Reality Testing

A crucial aspect of memory reconstruction is source monitoring, the process by which you determine the origin of your memories. Did you actually experience something, or did you just hear about it? Did you dream it, or did it really happen? This internal reality testing helps you distinguish between true memories, imagined events, and externally suggested information. When source monitoring fails, you can fall victim to “source amnesia,” forgetting where you learned a particular piece of information.

The Malleability of Memory: A Living, Breathing Record

Your memories are not static; they are dynamic and can be altered each time you retrieve them. This malleability, while essential for learning and adapting, also introduces the potential for inaccuracies. Think of your memories as a manuscript that is open to edits every time you read it.

Reconsolidation: The Opportunity for Update

Every time you retrieve a memory, it temporarily becomes “labile” or unstable. During this brief window, the process of reconsolidation occurs, where the memory is re-stabilized and stored again. This reconsolidation process is not merely a re-storing of the original memory; rather, it’s an opportunity for your brain to update or modify the memory trace based on new information or current emotional states. This means that each retrieval has the potential to subtly alter the memory, either strengthening certain details or integrating new, albeit sometimes erroneous, information.

Misinformation Effect and False Memories

The malleability of memory makes it susceptible to the misinformation effect. If you are exposed to misleading information after an event, your recall of that event can become distorted. For example, if you witness a car accident and are later asked “How fast were the cars going when they smashed into each other?” versus “How fast were the cars going when they hit each other?”, the verb choice can influence your estimate of the speed. In extreme cases, your brain can even construct entirely false memories, believing you experienced something that never actually occurred. These false memories can be incredibly vivid and feel authentic, highlighting the reconstructive and imaginative power of the brain.

The Impact of Suggestion and Leading Questions

Just as external factors can create false memories, they can also influence existing ones. Leading questions in interviews or suggestions from others can unconsciously reshape your recollections. This has significant implications in contexts such as eyewitness testimony, where the phrasing of questions can inadvertently lead to inaccurate accounts. You are not impervious to these influences; your brain strives for coherence, and sometimes that coherence is achieved by incorporating external suggestions.

The Adaptive Nature of Memory Reconstruction: Why Your Brain Does It

While the prospect of inaccurate memories might seem problematic, the reconstructive nature of memory is not a flaw; it is an incredible adaptive mechanism that serves several vital functions. It is like having a constantly evolving database, optimized for your current needs.

Cognitive Efficiency and Resource Management

Imagine if your brain stored every single sensory detail of every moment of your life. The sheer storage capacity required would be astronomical, and the retrieval process would be incredibly slow and cumbersome. By reconstructing memories, your brain effectively uses schemas and heuristics to create a coherent narrative, rather than retrieving a perfect, exhaustive record. This is a highly efficient way to manage cognitive resources, allowing you to quickly access relevant information without being bogged down by unnecessary details.

Learning, Adaptation, and Future Planning

The ability to update and modify memories through reconsolidation is crucial for learning and adaptation. When you learn new information, your brain can integrate it with existing memories, refining your understanding of the world. This dynamic process allows you to modify your behaviors and beliefs based on new experiences, ensuring that your knowledge base remains current and relevant. Furthermore, by reconstructing past events, you can simulate future scenarios, allowing you to plan and anticipate potential outcomes. Your brain uses past experiences as building blocks to construct potential futures, making you an effective planner and problem-solver.

Maintaining a Coherent Self-Narrative

Your memories are fundamental to your sense of identity. The reconstructive process plays a significant role in maintaining a coherent and consistent self-narrative. When you recall events from your past, your brain often subtly shapes them to align with your current self-perception and beliefs. This isn’t necessarily about intentional distortion, but rather a natural mechanism to create a cohesive story of who you are and how you came to be. This ability to integrate and interpret personal history is vital for psychological well-being.

The fascinating process by which the brain reconstructs memories has been the subject of extensive research, shedding light on how our past experiences shape our present. For a deeper understanding of this topic, you can explore a related article that delves into the intricacies of memory formation and retrieval. This article highlights the dynamic nature of memory and how it can be influenced by various factors. To read more about this captivating subject, visit Freaky Science.

Factors Influencing Memory Reconstruction: The Variables in Your Equation

| Metric | Description | Typical Value/Range | Relevance to Memory Reconstruction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hippocampal Activation | Level of activity in the hippocampus during memory recall | Moderate to High (measured via fMRI BOLD signal) | Critical for binding elements of a memory and reconstructing episodic details |

| Prefrontal Cortex Engagement | Degree of involvement of the prefrontal cortex in memory retrieval | Variable, often increased during complex recall tasks | Supports strategic retrieval and monitoring of reconstructed memories |

| Memory Distortion Rate | Percentage of recalled memories that contain inaccuracies or alterations | Up to 30% in some experimental conditions | Indicates the reconstructive nature and malleability of memory |

| Neural Pattern Similarity | Similarity index between encoding and retrieval neural patterns | Ranges from 0.4 to 0.8 (correlation coefficient) | Higher similarity suggests more accurate memory reconstruction |

| Reconsolidation Window | Time period after recall during which memories can be modified | Approximately 6 hours | Critical for updating or altering memories during reconstruction |

Many factors can influence the fidelity and accuracy of your memory reconstructions. Understanding these variables can provide insight into why your recollections may differ from others’ or even your own past accounts.

State-Dependent Memory

The context in which you encode a memory can significantly impact its retrieval. State-dependent memory suggests that you are more likely to recall information accurately if your internal physiological or psychological state at retrieval matches your state at encoding. If you studied for an exam while caffeinated, you might perform better on the exam if you are also caffeinated. Similarly, mood-congruent memory suggests that you are more likely to recall memories that align with your current mood—if you are feeling sad, you are more likely to remember other sad events.

The Passage of Time and Decay

Time is a powerful enemy of memory. As more time passes since an event, the memory trace can decay, and details can become fuzzier or lost altogether. This decay is not uniform; some aspects of a memory may be more resilient than others. With longer intervals, the brain has more opportunities to reconstruct and potentially alter the memory, sometimes leading to a less accurate recall.

Stress and Trauma

High levels of stress, particularly traumatic experiences, can significantly impact memory encoding and retrieval. While emotionally charged events are often vividly remembered (flashbulb memories), the details surrounding traumatic events can sometimes be fragmented, disorganized, or even repressed due to the overwhelming nature of the experience. The brain’s attempt to cope with trauma can lead to unusual memory patterns, highlighting the complex interplay between emotion, stress, and memory.

Age and Cognitive Decline

As you age, certain aspects of memory function can decline. This often manifests as difficulty with working memory, episodic memory (recalling specific events), and source memory. While semantic memory (general knowledge) tends to be more resilient, the reconstructive process can become less efficient, potentially leading to more errors or greater susceptibility to suggestion. However, this is not a universal decline, and individual variability is significant.

In conclusion, your memory is not a passive archive but an active, dynamic construction process. Each time you recall an event, you are essentially rebuilding it from fragments, influenced by your current knowledge, beliefs, and emotions. This reconstructive nature, while sometimes leading to inaccuracies, is a testament to the brain’s incredible capacity for adaptation, learning, and self-coherence. Understanding this process allows you to appreciate the complexity of your own mind and recognize the inherent subjectivity of your personal past.

FAQs

1. How does the brain reconstruct memories?

The brain reconstructs memories by piecing together stored information from various regions, such as the hippocampus and cerebral cortex. Instead of playing back exact recordings, the brain actively rebuilds memories each time they are recalled, integrating new information and context.

2. Why are memories sometimes inaccurate or distorted?

Memories can be inaccurate because the reconstruction process is influenced by current knowledge, emotions, and external suggestions. This can lead to alterations, omissions, or additions, making memories susceptible to distortion over time.

3. What role does the hippocampus play in memory reconstruction?

The hippocampus is crucial for retrieving and reconstructing episodic memories. It helps bind different elements of an experience—such as sights, sounds, and emotions—into a coherent memory that can be recalled later.

4. Can memory reconstruction be improved or trained?

While some aspects of memory reconstruction are automatic, techniques like mindfulness, focused attention, and memory training exercises can enhance recall accuracy. However, complete elimination of memory errors is not currently possible.

5. How does memory reconstruction affect eyewitness testimony?

Because memories are reconstructed and can be influenced by suggestion or stress, eyewitness testimony may be unreliable. This has important implications for legal settings, where memory distortions can lead to mistaken identifications or false recollections.