You’ve likely noticed it yourself, or perhaps observed it in a loved one: the subtle or sometimes jarring shifts in memory that accompany aging, illness, or injury. This phenomenon, often viewed with dread, is not always a sudden collapse but a more nuanced process known as graceful degradation. Imagine a magnificent old library where books are still present, but their indexing system is slowly failing. You can still find many volumes, but some are harder to locate, and occasionally, a whole section becomes inaccessible. This is the essence of graceful degradation: a system that continues to function, albeit with a diminished capacity, rather than experiencing abrupt failure.

To grasp the concept of graceful degradation in memory, you must first appreciate the intricate architecture of your own mind. Your memory isn’t a single, monolithic entity; it’s a sophisticated network of interconnected systems, each with specialized functions. You can learn more about split brain consciousness in this informative video.

The Multi-faceted Nature of Memory

Think of your memory as a grand orchestra. Each section—strings, brass, woodwinds, percussion—plays a distinct role, and all contribute to the overall symphonic experience.

Short-Term vs. Long-Term Memory

You have both transient and enduring memory stores. Short-term memory, often called working memory, is like a mental scratchpad. It allows you to hold a small amount of information in mind for a brief period, such as a phone number you’re about to dial. Long-term memory, conversely, is your vast archive of experiences, facts, and skills. This latter category is further subdivided.

Declarative vs. Non-Declarative Memory

Within long-term memory, you distinguish between what you know and what you do. Declarative memory is explicit and accessible to conscious recall. It includes:

- Episodic Memory: Your personal autobiography—events, experiences, and their specific contexts (e.g., what you ate for breakfast yesterday, your first kiss).

- Semantic Memory: Your mental encyclopedia—facts, concepts, and general knowledge (e.g., the capital of France, the meaning of “photosynthesis”).

Non-declarative memory, on the other hand, is implicit and often operates without conscious awareness. It encompasses:

- Procedural Memory: Your skills and habits (e.g., riding a bicycle, playing a musical instrument, tying your shoelaces).

- Priming: The subtle influence of prior exposure to a stimulus on your subsequent response.

- Classical Conditioning: Learned associations (e.g., salivating at the sound of a bell if you’ve been conditioned to associate it with food).

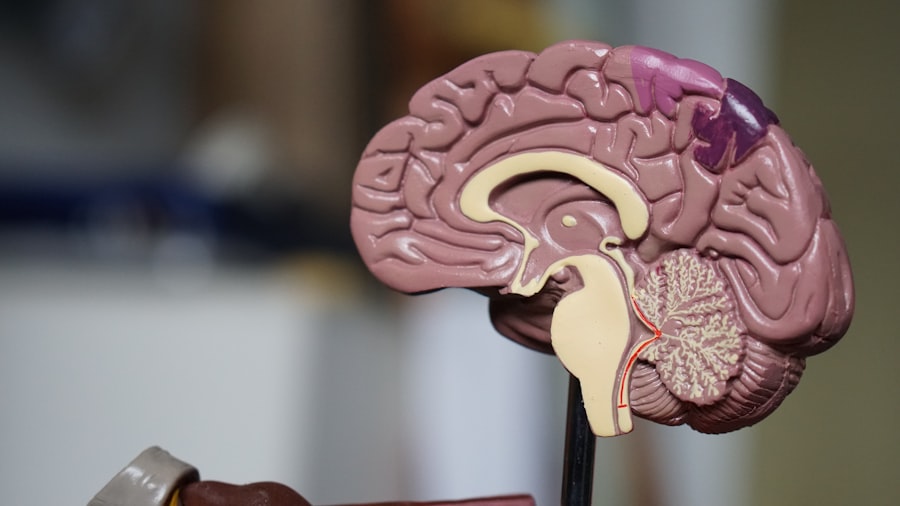

The Neurological Basis of Memory

Your memories are not stored in a single brain region but are distributed across intricate neural networks. The hippocampus, for instance, plays a crucial role in forming new episodic memories, acting like a central processing unit for new information. However, over time, these memories are believed to be consolidated and stored in various regions of the cerebral cortex. This distributed nature is a key factor in graceful degradation; a localized impairment might affect one type of memory more than others, much like a damaged section of a bridge only impacts a specific lane, not the entire structure.

Graceful degradation in the context of memory loss refers to the ability of a system to continue functioning even when parts of it fail or degrade over time. This concept is particularly relevant in discussions about cognitive decline and how individuals can adapt to memory challenges. For further insights into this topic, you can explore a related article that delves into the mechanisms of memory and strategies for coping with memory loss. Check it out here: Freaky Science.

Identifying the Signs of Graceful Degradation

You are a keen observer of your own mental landscape. Recognizing the subtle shifts is the first step in understanding and adapting to memory changes.

Common Manifestations of Memory Loss

The “symptoms” of memory degradation are diverse and can vary widely in their presentation and severity. They are often more apparent to others before you notice them yourself, particularly if they are gradual.

Difficulty with Recent Events

This is often one of the earliest and most noticeable signs. You might find yourself forgetting recent conversations, appointments, or where you placed everyday objects. It’s like a new inbox that isn’t always reliably saving emails.

Word-Finding Difficulties

The “tip-of-the-tongue” phenomenon becomes more frequent. You know the word, you can even describe it, but retrieving it feels like trying to pull a specific book from a dimly lit shelf. This is known as anomia.

Challenges with Multitasking and Planning

Tasks that once seemed effortless, such as preparing a complex meal or managing a schedule, might become overwhelming. This often indicates a decline in executive functions, which are closely linked to working memory.

Repetitive Questioning

You might find yourself, or a loved one, asking the same question multiple times within a short period, unaware that the answer has already been provided. This is often characteristic of impaired short-term memory encoding.

Differentiating Normal Aging from Pathological Conditions

It’s crucial to understand that not all memory changes signify disease. Some degree of cognitive decline is a natural part of aging, akin to your skin losing elasticity or your hair graying.

Age-Associated Memory Impairment (AAMI)

You might experience AAMI as you age. This involves subjective memory complaints without significant impairment in daily functioning. It’s often characterized by slower processing speed and minor difficulty recalling names or dates, but it doesn’t typically progress to dementia. Think of it as a well-worn path that takes a little longer to traverse.

Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI)

MCI represents a transitional stage between normal aging and dementia. You or others might notice a more noticeable decline in one or more cognitive domains (e.g., memory, language, attention) that is greater than expected for your age, but it does not yet interfere significantly with your independence in daily life. A percentage of individuals with MCI will progress to dementia, while others will not, or may even improve.

Dementia

Dementia, unlike AAMI or MCI, is a syndrome characterized by a significant decline in cognitive function that is severe enough to interfere with daily activities and independence. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia, but other forms exist, such as vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia, and frontotemporal dementia. In these cases, the degradation is more pervasive and impacts a wider range of cognitive abilities, moving from specific lane closures to major roadworks across your mental landscape.

Strategies for Coping and Adaptation

When faced with memory changes, your proactive engagement in coping and adaptation strategies can significantly enhance your quality of life and potentially slow the progression of decline. This is where you become the architect of your own cognitive resilience.

Cognitive Reserve and Brain Health

Your brain possesses an amazing capacity for plasticity and resilience, collectively known as cognitive reserve. This is like having extra resources and alternative pathways in your mental library; if one section becomes difficult to access, you have built other routes to retrieve information.

Maintaining an Active Lifestyle

Physical activity has a profound impact on brain health. Regular exercise increases blood flow to the brain, promotes the growth of new brain cells, and reduces the risk of cardiovascular diseases that can contribute to cognitive decline. Think of it as regularly maintaining and upgrading the infrastructure of your mental city.

Engaging in Lifelong Learning

Continuously challenging your brain with new information and skills helps build cognitive reserve. Learning a new language, solving complex puzzles, playing a musical instrument, or pursuing a new hobby all contribute to creating new neural pathways and strengthening existing ones. This is akin to constantly adding new wings and expanding the catalog of your mental library.

Social Interaction and Engagement

Maintaining strong social connections is vital for cognitive health. Social interaction stimulates various brain regions, reduces stress, and combats feelings of isolation and depression, which can negatively impact memory. Consider your social network as a team of librarians, collaboratively organizing and accessing information.

Memory Aids and Assistive Technologies

You don’t have to face memory challenges alone. A plethora of tools and strategies can help you compensate for difficulties and maintain independence.

External Memory Aids

These are your practical, everyday tools. Calendars, diaries, notebooks, sticky notes, and voice recorders can serve as external repositories for information you might otherwise forget. Setting alarms and reminders on your phone for appointments or medication is another effective strategy. These are like having a personal assistant constantly reminding you of your schedule.

Environmental Modifications

Structuring your environment in a consistent and predictable way can significantly reduce memory demands. Keeping frequently used items in designated places, labeling cupboards and drawers, and organizing your living space can minimize the cognitive load of searching for things. This is like having a meticulously organized library where every book has its specific home.

Technological Solutions

Smartphones and tablets offer a wide array of apps for reminders, note-taking, and cognitive exercises. GPS devices can assist with navigation, reducing the burden on spatial memory. Voice assistants can provide quick access to information and help manage daily tasks. These are powerful digital tools that can augment your natural memory functions.

Lifestyle Adjustments and Stress Management

Your overall well-being profoundly impacts your cognitive function. Addressing lifestyle factors and managing stress are crucial components of coping with memory changes.

Healthy Diet

A balanced diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and healthy fats (like those found in fish and nuts) supports brain health. The Mediterranean diet, in particular, has been associated with a lower risk of cognitive decline. Think of it as providing your mental library with the high-quality nutrients it needs to operate optimally.

Sufficient Sleep

Quality sleep is essential for memory consolidation. During sleep, your brain actively processes and stores memories from the day. Chronic sleep deprivation can impair cognitive function and memory. Ensure you prioritize consistent and restorative sleep. This is when your mental librarian meticulously shelves all the new books from the day.

Stress Reduction Techniques

Chronic stress can have detrimental effects on the brain, including impacting memory. Practicing mindfulness, meditation, yoga, or engaging in hobbies that you find relaxing can help reduce stress levels and protect cognitive function. This is about creating a calm and conducive environment for your mental endeavors, preventing your library from becoming chaotic.

Graceful degradation in memory loss is a fascinating topic that explores how the brain can still function despite the gradual decline of certain cognitive abilities. For a deeper understanding of this phenomenon, you might find the article on memory and its complexities particularly insightful. It discusses various aspects of memory retention and loss, shedding light on how our cognitive systems adapt over time. You can read more about it in this related article that delves into the intricacies of memory and its resilience.

Focusing on Strengths and Meaningful Living

| Metric | Description | Typical Values | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Memory Retention Rate | Percentage of information retained over time despite degradation | 60% – 85% after 1 week | Standardized memory recall tests |

| Rate of Memory Loss | Speed at which memory deteriorates in graceful degradation | 5% – 15% per month | Longitudinal cognitive assessments |

| Functional Impact Score | Degree to which memory loss affects daily activities | Low to Moderate (1-3 on a 5-point scale) | Clinical interviews and questionnaires |

| Neural Plasticity Index | Brain’s ability to adapt and compensate for memory loss | Variable; higher in younger individuals | Neuroimaging and electrophysiological studies |

| Compensatory Strategy Usage | Frequency of using memory aids or alternative strategies | Moderate to High | Self-report and behavioral observation |

As memory degradation progresses, it’s vital to shift your focus from solely what is being lost to what remains and how you can continue to live a life of purpose and enjoyment. You are more than your memories; you are a person with skills, passions, and a unique history.

Emphasizing Remaining Abilities

Even as some cognitive functions decline, others may remain relatively intact. Procedural memory (e.g., playing a musical instrument, cooking a familiar recipe, engaging in a cherished craft) is often preserved longer than episodic memory. Encourage engagement in activities that draw upon these enduring strengths. This is like appreciating the beautiful and functional sections of your library that are still flourishing.

Maintaining Social Engagement

Despite memory challenges, continuing to connect with family and friends is paramount. Social interaction provides emotional support, reduces feelings of isolation, and can still be a source of joy and stimulation. Adapt activities to suit current abilities, focusing on quality interaction over complex communication.

Finding Purpose and Enjoyment

Even with memory loss, you can still find activities that bring meaning and happiness. This could involve simple pleasures like listening to music, spending time in nature, engaging in gentle exercise, or participating in simplified versions of hobbies you once enjoyed. The goal is to cultivate a life that, while altered, remains rich in positive experiences. This is about finding new ways to enjoy the stories and experiences within your library, even if some sections are less accessible.

The Role of Support Systems

You are not alone in this journey. Building a robust support system is instrumental for both the individual experiencing memory loss and their caregivers.

Family and Friends

Loved ones play a critical role in providing practical assistance, emotional support, and understanding. Educating family and friends about graceful degradation, its nuances, and effective communication strategies can foster a more supportive environment.

Healthcare Professionals

Regular consultation with doctors, neurologists, and neuropsychologists is essential for accurate diagnosis, monitoring, and management. They can offer guidance on medication, cognitive therapies, and connect you with local resources.

Support Groups and Community Resources

Connecting with others who are facing similar challenges can provide invaluable support, shared coping strategies, and a sense of community. Organizations dedicated to memory loss and dementia often offer educational programs, support groups, and respite services.

Ultimately, graceful degradation is a testament to the brain’s remarkable adaptability. While some pathways may become less efficient, and certain memories harder to access, your brain often finds alternative routes and compensates in subtle ways. By understanding these processes, adopting proactive strategies, and building strong support systems, you can navigate memory changes with resilience, maintaining your dignity and continuing to live a meaningful life. The library may be aging, and some sections less frequented, but its vast collection, intricate architecture, and enduring spirit remain.

FAQs

What is graceful degradation in the context of memory loss?

Graceful degradation refers to the gradual decline in memory function rather than a sudden loss. It describes how cognitive abilities deteriorate slowly over time, allowing individuals to maintain some level of memory performance despite progressive impairment.

How does graceful degradation differ from sudden memory loss?

Graceful degradation involves a slow and steady decline in memory capabilities, often associated with aging or neurodegenerative diseases. Sudden memory loss, on the other hand, occurs abruptly due to events like trauma, stroke, or acute medical conditions.

What causes graceful degradation of memory?

Graceful degradation of memory is commonly caused by natural aging processes, mild cognitive impairment, or early stages of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease. It results from gradual neuronal loss, synaptic dysfunction, and changes in brain plasticity.

Can graceful degradation of memory be slowed or prevented?

While it may not be entirely preventable, certain lifestyle factors like regular physical exercise, cognitive training, a healthy diet, and managing cardiovascular risk factors can help slow the progression of memory decline associated with graceful degradation.

How is graceful degradation of memory diagnosed?

Diagnosis typically involves clinical assessments, cognitive testing, and sometimes neuroimaging to evaluate the extent and pattern of memory decline. Healthcare professionals look for gradual changes in memory performance over time to distinguish graceful degradation from other types of memory loss.