You are undoubtedly familiar with the concept of memory in the biological brain: a complex, distributed system where information isn’t stored in isolated lockers but rather across networks of interconnected neurons. This biological paradigm has long fascinated researchers, and in the realm of artificial intelligence, it has inspired a particularly promising and increasingly relevant field: Distributed Memory Encoding Neural Networks (DMENNs). Unlike traditional neural network architectures that often rely on concentrated, localized representations of information, DMENNs embrace a more diffuse, interwoven approach, mirroring the intricate storage mechanisms observed in biological systems. You might think of it as the difference between labeling individual files in a neatly organized cabinet versus embedding fragments of information across countless interwoven strands of a vast, digital tapestry.

The Foundations of Distributed Memory Encoding

To grasp the significance of DMENNs, you must first understand the fundamental principles that underpin their design. These principles deviate from some conventional neural network paradigms, offering distinct advantages for specific computational challenges. You can learn more about split brain consciousness in this informative video.

From Localized to Diffuse Representations

In many artificial neural networks, especially earlier iterations, concepts are frequently encoded in a localized manner. A single neuron, or a small cluster of neurons, might be responsible for recognizing a specific feature or representing a particular semantic concept. For example, a neuron might activate strongly when it “sees” an edge at a particular angle. While effective for certain tasks, this localization can lead to vulnerabilities. If that specific neuron or cluster is damaged or fails, the capacity to recognize that feature is lost.

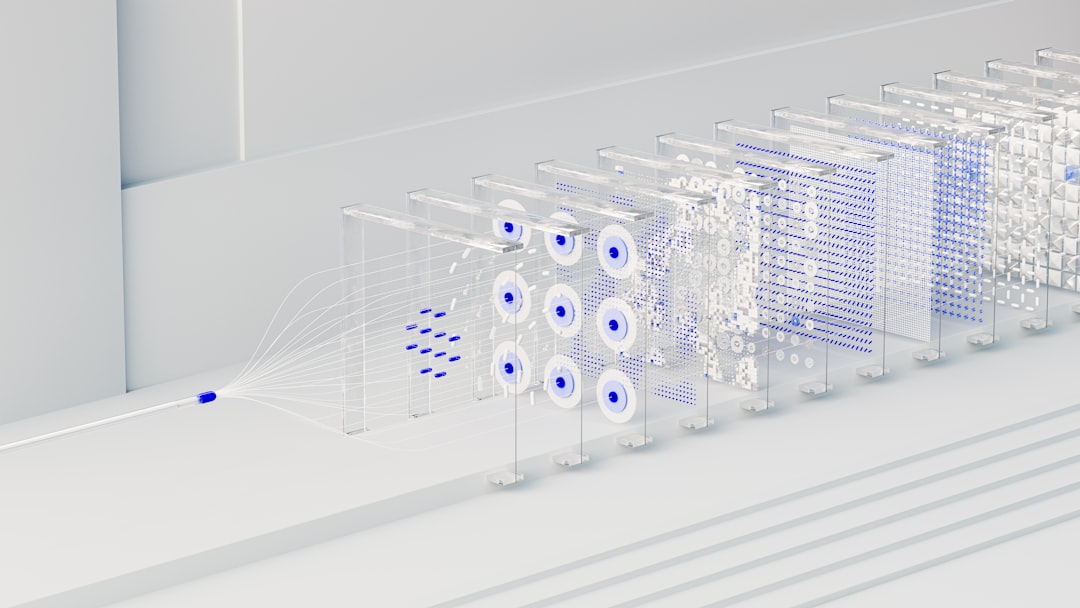

DMENNs, conversely, operate on the principle of diffuse representation. Imagine a mosaic where no single tile holds the entirety of an image, but rather the collective arrangement of many tiles forms the complete picture. In a DMENN, information about a concept – say, the concept of “cat” – is not stored in one dedicated node. Instead, it is distributed across a large number of interconnected neurons. Each neuron contributes only a small, partial piece of the overall representation. This distributed nature provides an inherent robustness; damage to a few neurons does not obliterate the entire concept but rather subtly degrades its representation. It’s like losing a few pixels from a high-resolution image; the overall picture remains discernible.

The Role of Activation Patterns

Central to distributed memory encoding is the concept of activation patterns. You might visualize these as unique “fingerprints” of neural activity. When a DMENN processes information, specific patterns of activation emerge across its network. These patterns are not static; they are dynamic and responsive to input. A particular activation pattern might correspond to a specific memory, concept, or piece of information. The network learns to associate these patterns with inputs and outputs, establishing connections that enable retrieval and recall.

Consider a simple analogy: imagine a complex switchboard with thousands of lights. Each light can be either on or off. A specific arrangement of lit and unlit bulbs represents a particular piece of data. When you want to “recall” that data, the network attempts to recreate that specific configuration of lights. The more distinct the patterns, the more information the network can store and differentiate.

Associative Memory and Hebbian Learning

DMENNs are heavily influenced by theories of associative memory, particularly Hebbian learning. Hebbian theory, succinctly summarized as “neurons that fire together wire together,” posits that the synaptic connections between neurons strengthen when they are simultaneously active. This principle is a cornerstone of how DMENNs acquire and store information.

When two pieces of information are presented to the network simultaneously or in close temporal proximity, the neurons representing those pieces of information tend to activate together. Over time, in accordance with Hebbian learning rules, the connections between these co-activating neurons are reinforced. This strengthening of connections forms the basis of association. When one piece of information is later presented, it can activate the associated neurons, thereby “recalling” the other piece of information. You might think of it as creating enduring pathways in a forest; the more frequently you traverse two paths together, the more defined and interconnected they become.

Architectural Innovations and Common Models

While the core principles remain consistent, DMENNs manifest in various architectural forms, each with its own strengths and applications. You will encounter several key models that exemplify the distributed memory paradigm.

Hopfield Networks: Early Pioneers

One of the earliest and most influential models demonstrating distributed memory encoding is the Hopfield network. Introduced by John Hopfield in the early 1980s, these are recurrent artificial neural networks where each neuron is connected to every other neuron. The network’s state is defined by the activation pattern of its neurons.

Hopfield networks are primarily used as associative memory systems. You can train a Hopfield network to store specific patterns (memories). When presented with a noisy or incomplete version of a stored pattern, the network iteratively updates the states of its neurons until it converges to the closest stored memory. This self-correction mechanism is a direct consequence of the distributed encoding. The network effectively acts as an error-correcting code, making it robust to partial or corrupted input. Imagine having fragmented pieces of a photograph; a Hopfield network can piece them together to reconstruct the original image.

Self-Organizing Maps (SOMs): Unsupervised Clustering

Another significant DMENN architecture is the Self-Organizing Map (SOM), developed by Teuvo Kohonen. Unlike Hopfield networks, SOMs are unsupervised learning algorithms, meaning they learn from unlabeled data without explicit guidance. SOMs are particularly good at visualizing high-dimensional data by mapping it onto a low-dimensional (typically two-dimensional) grid of neurons.

Each neuron in a SOM has a “weight vector” that represents a point in the input space. When an input vector is presented to the network, the neuron whose weight vector is most similar to the input vector becomes the “winner.” This winning neuron, along with its neighbors, then updates its weights to become even more similar to the input. Over many iterations, the SOM organizes itself such that similar input vectors activate spatially close neurons on the map. This creates a “topographical map” where adjacent regions represent similar concepts. You can think of it as a geographical map where cities with similar climates are grouped together, even though they may be geographically distant in reality.

Sparse Distributed Memory (SDM): Content-Addressable Storage

Sparse Distributed Memory (SDM), proposed by Pentti Kanerva, offers a compelling approach to content-addressable memory. In contrast to location-addressable memory (where you retrieve data by knowing its address), content-addressable memory retrieves data based on its content. This is analogous to remembering a book by recalling a phrase from it rather than its shelf number.

SDM utilizes a very high-dimensional address space, but only a sparse subset of these addresses are “hard addresses” where information can be directly stored. When you write a memory to an SDM, it is not stored at a single hard address. Instead, it is distributed across multiple hard addresses that are “close” to the input address in the high-dimensional space. When you later attempt to recall a memory, you provide a retrieval address. The SDM then activates all hard addresses that are sufficiently close to the retrieval address and collectively reconstructs the stored information from these activated locations. This distribution makes the memory robust to noise and partial cues. Imagine spreading out a message across many different post-it notes, each in a slightly different but related location. When you want to read the message, you gather all the post-it notes within a certain radius and combine their content.

Advantages of Distributed Memory Encoding

You might be wondering about the tangible benefits of this distributed approach. DMENNs offer several compelling advantages over more localized or centralized memory systems in artificial intelligence.

Robustness and Fault Tolerance

Perhaps the most immediately evident advantage is enhanced robustness and fault tolerance. As you’ve seen, information in a DMENN is spread across numerous processing units. This means that if a small number of neurons are damaged or fail, the overall integrity of the stored information is not severely compromised. The remaining neurons can often still collectively represent and retrieve the information, albeit potentially with slight degradation. This redundancy is a significant asset in real-world applications where hardware failures or noisy input are common. It’s like having a backup system inherently built into the very architecture of the memory.

Generalization and Transfer Learning

DMENNs naturally exhibit strong generalization capabilities. Because concepts are represented by overlapping patterns of activity rather than discrete symbols, the network can often correctly interpret novel inputs that bear a resemblance to previously learned ones. When a DMENN learns about “dogs,” it learns a distributed pattern that encompasses various dog breeds, sizes, and appearances. When presented with a dog it has never seen before, it can still activate a similar pattern, leading to correct identification.

This also contributes to impressive performance in transfer learning scenarios. Knowledge acquired in one domain can often be partially repurposed for a related domain because the underlying distributed representations encode fundamental features and relationships that are applicable more broadly. Think of it as learning the grammar of a language; once you understand the underlying rules, you can apply them to form new, previously unheard sentences.

Capacity and Scalability

While it might seem counterintuitive, distributed encoding can lead to a more efficient use of memory resources and a higher storage capacity. Because each neuron can participate in the encoding of multiple different memories, the network’s capacity to store information is not limited by the number of neurons but by the number of distinguishable activation patterns it can generate. This allows for a massive number of memories to be stored within a relatively compact network.

Furthermore, DMENNs often exhibit better scalability. As the amount of data increases, you don’t necessarily need to add a proportionally huge number of specialized memory units. Instead, the existing network can adapt by forming more nuanced and complex distributed patterns.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite their significant promise, DMENNs are not without their challenges. As you delve deeper, you’ll encounter areas where further research and development are crucial.

Interpretability and “Black Box” Problem

One persistent challenge across many advanced neural network architectures, including DMENNs, is interpretability. Because information is so diffusely encoded, it can be difficult to pinpoint precisely why a network made a particular decision or how a specific memory is stored. The “black box” problem, where the internal workings of the network are opaque, remains a significant hurdle. Understanding and developing methods to visualize and interpret these distributed representations is an active area of research. You want to not only know what the network did but how and why it did it.

Training Complexity and Convergence

While DMENNs offer advantages in some areas, training them can sometimes be more complex than training more localized networks. The interactions between widely distributed neurons can lead to intricate optimization landscapes, making it challenging to ensure effective learning and convergence to stable, meaningful representations. Developing more robust and efficient training algorithms remains a key focus.

Integration with Hybrid Systems

The future of AI often lies in hybrid systems that combine the strengths of different approaches. Integrating DMENNs with symbolic AI systems, which excel at logical reasoning and structured knowledge representation, presents a fascinating and promising avenue. Imagine a system where the intuitive, associative memory of a DMENN is paired with the logical deduction capabilities of a symbolic AI. This could lead to genuinely intelligent systems capable of both pattern recognition and abstract reasoning.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy and Future Impact

You have explored the fascinating world of Distributed Memory Encoding Neural Networks, a revolutionary approach to artificial intelligence inspired by the biological brain. From the foundational principles of diffuse representations and activation patterns to the innovative architectures like Hopfield networks and SDMs, DMENNs offer a compelling alternative to traditional neural network designs. Their inherent robustness, generalization capabilities, and impressive storage capacity position them as a cornerstone for future advancements in fields such as natural language processing, computer vision, and cognitive computing.

While challenges in interpretability and training complexity persist, the continuous innovation in this field promises to unlock even greater potential. As you consider the vast landscapes of artificial intelligence, DMENNs offer a reminder that sometimes, the most profound insights come from distributed, interwoven intelligence, mirroring the very fabric of our own complex minds. The journey to truly intelligent machines will undoubtedly continue to be paved with the insights gained from understanding how information can be effectively, and robustly, distributed across countless interconnected processing units.

FAQs

What are distributed memory encoding neural networks?

Distributed memory encoding neural networks are computational models designed to store and retrieve information across a network of interconnected neurons. Instead of storing data in a single location, information is encoded in patterns of activity distributed throughout the network, allowing for robust memory representation.

How do distributed memory encoding neural networks differ from traditional memory models?

Unlike traditional memory models that rely on localized storage, distributed memory encoding neural networks use a collective representation where each neuron participates in encoding multiple memories. This distributed approach enhances fault tolerance and generalization capabilities.

What are common applications of distributed memory encoding neural networks?

These networks are commonly applied in areas such as pattern recognition, associative memory tasks, cognitive modeling, and machine learning systems that require robust and efficient memory storage and retrieval mechanisms.

What types of neural network architectures support distributed memory encoding?

Architectures such as Hopfield networks, recurrent neural networks (RNNs), and certain types of autoencoders are known to support distributed memory encoding by leveraging their recurrent connections and dynamic activity patterns.

What are the advantages of using distributed memory encoding in neural networks?

Advantages include increased robustness to noise and damage, the ability to generalize from partial inputs, efficient storage of large amounts of information, and improved fault tolerance compared to localized memory storage systems.