Welcome, curious mind, to an exploration of a phenomenon that has, at some point, undoubtedly touched your own experience: déjà vu. You’ve been there, haven’t you? A sudden, potent sense of having lived this very moment before, even though intellectually you know it’s brand new. This isn’t a glitch in the Matrix; it’s a fascinating, albeit sometimes unsettling, manifestation of your brain’s intricate workings. Today, we’ll delve into the neuroscience underpinning this transient yet profound feeling of familiarity, dissecting the theories and anatomical pathways that attempt to explain it. Prepare to navigate the labyrinthine corridors of your own memory and perception.

Before we dissect the mechanisms, it’s crucial to establish a common understanding of what constitutes déjà vu. The term itself, French for “already seen,” was coined by French psychiatrist Émile Boirac in 1876. You might initially associate it with a fleeting visual experience, but déjà vu is far more encompassing. It can manifest as “déjà vécu” (already lived), “déjà senti” (already felt), or even “déjà entendu” (already heard). The core characteristic, however, remains consistent: an overwhelming subjective sensation of familiarity with a new experience, coupled with the rational knowledge that this familiarity is anomalous. You’re not actually remembering a past event; you’re feeling like you are. This distinction is vital for understanding its neurological roots. You can learn more about split brain consciousness by watching this insightful video.

The Subjective Experience: More Than Just a Feeling

When you encounter déjà vu, it’s not a mere passing thought. It often carries an emotional weight, a fleeting sense of oddity or even mild disorientation. You might find yourself searching for a “trigger,” trying to pinpoint the exact moment or detail that sparked the feeling. This introspective effort highlights the conscious awareness that accompanies the phenomenon. It’s not a subconscious process; it actively engages your higher cognitive functions as you grapple with the contradiction between your subjective experience and objective reality.

Prevalence and Demographics: Who Experiences It?

Déjà vu is surprisingly common. Studies suggest that between 60% and 80% of healthy individuals experience it at some point in their lives, with its frequency typically peaking in young adulthood and then gradually declining with age. This age-related decline is a significant clue, hinting at the involvement of cognitive functions that might be more robust in younger brains. While there are no discernable demographic differences in terms of gender or cultural background, its prevalence in epileptic patients, particularly those with temporal lobe epilepsy, offers a crucial window into its potential neurological underpinnings.

Déjà vu is a fascinating phenomenon that has intrigued both scientists and the general public alike, often leading to discussions about the workings of the human brain. For a deeper understanding of the neuroscience behind déjà vu, you can explore an insightful article that delves into the cognitive processes and potential explanations for this mysterious experience. To read more about it, visit Freaky Science, where you can find a wealth of information on various intriguing scientific topics.

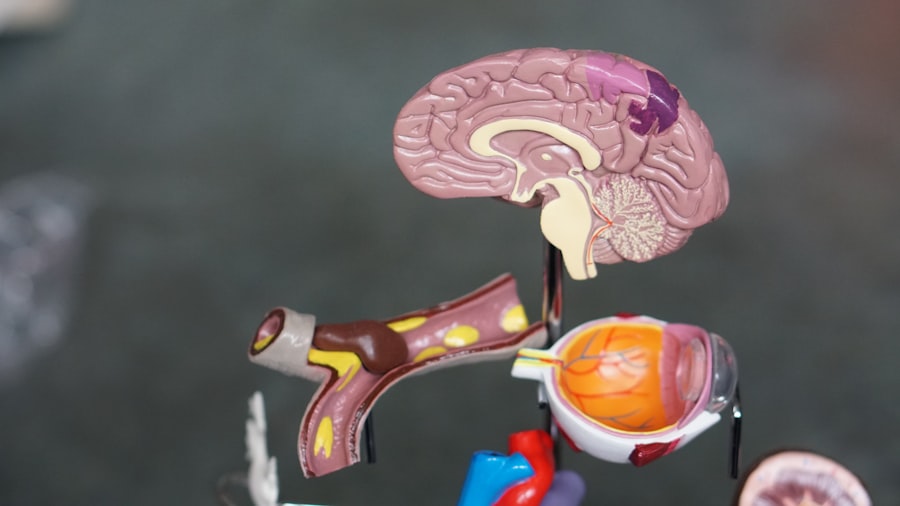

The Temporal Lobe: A Key Player in Familiarity Circuits

If you were to pinpoint a single region of the brain most frequently implicated in déjà vu, your target would undoubtedly be the temporal lobe. Consider it the central command post for memory formation, retrieval, and the processing of emotional information. Within this crucial lobe, specific structures play particularly prominent roles in creating the intricate tapestry of our remembered experiences and our sense of “knowing.”

The Hippocampus: Architect of New Memories

Imagine your hippocampus as a meticulous librarian, diligently cataloging every new piece of information you encounter. It’s a vital structure for the formation of new declarative memories – the facts and events you can consciously recall. Damage to the hippocampus, as seen in amnesia, severely impairs the ability to form new memories, demonstrating its critical role in learning. In the context of déjà vu, some theories propose that a fleeting misfire or temporary disruption in hippocampal activity could lead to a momentary sense of an old memory being retrieved, even when no such memory exists. It’s like the librarian accidentally pulling out an empty file and mistakenly assuming it contains a familiar record.

The Rhinal Cortex: The Familiarity Detector

Adjacent to the hippocampus, you’ll find the rhinal cortex, a region often subdivided into the entorhinal and perirhinal cortices. While the hippocampus excels at detailed, episodic memory (recalling where and when an event occurred), the rhinal cortex appears to be more involved in a more abstract sense of familiarity – the feeling of “knowing” something without necessarily recalling specific details. Think of it as a less precise but faster recognition system. If you see a face and simply know you’ve seen it before, even if you can’t remember their name or where you encountered them, that’s the rhinal cortex at work. In déjà vu, it’s hypothesized that a transient overactivation or misfiring in the rhinal cortex could generate this feeling of familiarity in the absence of genuine prior exposure, effectively issuing a false positive.

The Amygdala: The Emotional Tint

Nestled deep within the temporal lobes, the amygdala is your brain’s emotional alarm system. It’s responsible for processing emotions, particularly fear and pleasure, and imbuing memories with an emotional charge. When you experience déjà vu, it often comes with a distinct emotional tang – a feeling of unease or even surprise. This emotional component suggests the amygdala might be involved, perhaps by reacting to the conflicting signals arriving from other memory structures. It’s as if the amygdala is receiving a “familiarity alert” from the rhinal cortex but no corresponding “memory recall” signal from the hippocampus, creating an emotional dissonance.

Theories of Dysfunctional Memory Processing: When the System Glitches

The most widely accepted explanations for déjà vu center on temporary disruptions or misfirings within the brain’s memory systems. It’s not necessarily a sign of pathology in healthy individuals, but rather an occasional, benign hiccup in the otherwise finely tuned machinery of memory consolidation and retrieval. These theories offer different perspectives on how this “hiccup” manifests.

Divided Attention Theory: A Brief Moment of Unawareness

Consider a scenario where you’re walking into a room. You might initially glance at something – a painting on the wall, a distinctive piece of furniture – but your attention is divided. Perhaps you’re deeply engrossed in a thought or distracted by a conversation. A brief, unconscious processing of that visual information occurs without your full attention. Later, when you consciously focus on the painting or furniture, your brain recognizes the previously, subtly processed information, but because the initial encoding was so fleeting and lacked conscious awareness, it’s interpreted as a completely new experience that paradoxically feels familiar. It’s like seeing a blurry image and then, when it comes into focus, feeling like you “saw” it clearly before, even though you didn’t.

Dual Processing Theory: A Synchronization Error

This theory proposes that déjà vu arises from a momentary desynchronization between two key cognitive processes involved in recognition: recall and familiarity. Recall is the conscious retrieval of specific details about a past event, whereas familiarity is a general sense of knowing without specific details. Under normal circumstances, these processes work in harmony. However, in déjà vu, it’s suggested that the familiarity system fires prematurely or independently, generating a strong sense of “I know this!” before the recall system has had a chance to confirm or deny the experience with actual memory traces. It’s akin to having a music player where the “familiarity” button glows brightly, signaling a recognized tune, but the “recall” button remains dim, unable to provide the song’s title or artist.

Transient Neuronal Misfiring: An Electrical Storm in Miniature

Drawing insights from epilepsy research, another prominent theory posits that déjà vu could be caused by a momentary, localized electrical disturbance in the temporal lobe – a miniature, non-epileptic seizure. In individuals with temporal lobe epilepsy, déjà vu is a common aura preceding a seizure, suggesting a direct link to abnormal neuronal activity. For healthy individuals, this “misfiring” might be a much milder and self-correcting event, too subtle to be categorized as a seizure but potent enough to disrupt the delicate balance of memory processing, leading to the sensation of déjà vu. Imagine a fleeting power surge in your home’s electrical system; it doesn’t cause a blackout, but it might flicker the lights momentarily.

Psychological Perspectives: Beyond Wiring and Firing

While neuroscience provides a valuable framework for understanding the brain’s role in déjà vu, psychological theories offer complementary insights, exploring the cognitive biases and perceptual tricks that might contribute to this phenomenon. These perspectives often intertwine with neurological explanations, providing a more holistic view.

Configuration Familiarity: The Shapes of Things

Sometimes, déjà vu isn’t about the specific content of an experience but rather the configuration or layout of elements within it. Imagine walking into an unfamiliar room that, structurally – the arrangement of doors, windows, and dominant furniture – resembles a room you’ve encountered before. Your brain, in its efficiency, might encode the spatial configuration rather than the individual objects. When you subsequently encounter a new room with a similar spatial layout, your brain retrieves that configurational memory, triggering the sense of familiarity, even though the specific details are new. It’s like recognizing a musical chord progression even if the instruments playing it are entirely different.

Attention and Perceptual Processing: The Illusion of Continuity

This perspective emphasizes how our attention can selectively filter information, leading to gaps in our conscious awareness. If you briefly glimpse a scene without fully processing it, and then your attention shifts to fully absorb it, your brain might interpret the current, complete perception as a re-encounter with the fragmented, partially processed initial glimpse. This creates an illusion of having experienced it before, even though you were only consciously aware of it the second time. Think of it as a movie reel where a few frames are accidentally skipped; when the movie plays again, you experience a momentary jump that feels like a repeat, even though the content is still progressing.

Recent studies in neuroscience have provided intriguing insights into the phenomenon of déjà vu, suggesting that it may be linked to the brain’s memory processing systems. For a deeper understanding of this captivating subject, you can explore a related article that delves into the mechanisms behind these fleeting experiences. The article discusses how certain brain regions, particularly the temporal lobe, play a crucial role in the sensation of familiarity. To read more about this fascinating topic, check out the article here.

Exploring the Future: Research Directions and Open Questions

| Metric | Description | Value/Range | Source/Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of Déjà Vu | Percentage of people experiencing déjà vu at least once | 60-80% | Brown, 2004 |

| Brain Region Involved | Primary area linked to déjà vu experiences | Temporal Lobe (especially the hippocampus) | O’Connor et al., 2010 |

| Neural Mechanism | Proposed cause of déjà vu in neuroscience | Mismatch between familiarity and recollection processes | Cleary et al., 2009 |

| EEG Activity | Brainwave patterns observed during déjà vu | Increased theta activity in temporal regions | Adachi et al., 2006 |

| Duration of Experience | Typical length of a déjà vu episode | 1-10 seconds | Brown, 2004 |

| Age of Onset | Common age range when déjà vu starts occurring | 15-25 years | Wild, 2005 |

| Relation to Epilepsy | Déjà vu as a symptom in temporal lobe epilepsy | Occurs in ~50% of temporal lobe epilepsy patients | Spatt, 2002 |

Despite significant strides, the neuroscience of déjà vu remains an active and evolving field of research. While we have a strong understanding of the implicated brain regions and plausible mechanisms, many questions persist.

Imaging Techniques: Peering Deeper into the Brain

Advancements in neuroimaging techniques, such as fMRI (functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging) and EEG (Electroencephalography), offer increasingly sophisticated ways to observe brain activity in real-time. Researchers are employing these tools to identify the precise neural correlates of déjà vu as it occurs in healthy individuals. The challenge lies in capturing such a fleeting and unpredictable phenomenon in a controlled laboratory setting. Imagine trying to photograph a rare butterfly that lands for only a split second; you need to be quick and precise.

Computational Models: Simulating the Familiarity Circuit

Developing computational models of memory and recognition allows researchers to simulate different scenarios of neuronal activity and test hypotheses about déjà vu. By manipulating parameters within these models, scientists can explore how misfires or desynchronization in specific neural circuits might lead to the subjective experience of familiarity. These models act as digital laboratories, enabling exploration of complex interactions that are difficult to isolate within the living brain.

The Link to Memory Disorders: A Window into Normal Function

Investigating déjà vu in individuals with certain neurological conditions, particularly those involving memory impairments, can provide invaluable insights into the normal functioning of memory systems. Understanding how and why déjà vu manifests differently in these populations can shed light on the fundamental processes that govern our sense of familiarity and recollection. For instance, studying déjà vu in patients with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease might reveal subtle deficits in memory processing that contribute to the phenomenon.

In conclusion, you’ve journeyed through the intricate landscape of your own brain, exploring the complex interplay of memory, perception, and emotion that gives rise to the elusive phenomenon of déjà vu. It’s not a supernatural event or a momentary glimpse into a past life, but rather a compelling example of how your brain, in its tireless effort to make sense of the world, can sometimes play a subtle trick on your conscious awareness. The next time you experience that uncanny sensation, remember the rhinal cortex, the hippocampus, and the fascinating, albeit imperfect, mechanisms that produce that fleeting, familiar feeling. You are truly a product of your brain’s remarkable, and sometimes quirky, design.

FAQs

What is déjà vu from a neuroscience perspective?

Déjà vu is a phenomenon where a person feels that a current experience has been lived before. Neuroscientifically, it is thought to result from a temporary glitch in the brain’s memory systems, particularly involving the temporal lobe and hippocampus, which causes a feeling of familiarity without a clear memory.

Which brain areas are involved in déjà vu?

The temporal lobe, especially the hippocampus and parahippocampal gyrus, are key brain regions involved in déjà vu. These areas are responsible for processing memories and spatial navigation, and their temporary dysfunction or miscommunication may trigger the sensation of déjà vu.

Is déjà vu linked to any neurological conditions?

Yes, déjà vu is commonly reported in people with temporal lobe epilepsy. In these cases, déjà vu can be a type of aura or warning sign before a seizure. However, in healthy individuals, déjà vu is generally harmless and occurs sporadically without underlying neurological disease.

What causes the feeling of familiarity in déjà vu?

The feeling of familiarity in déjà vu may arise from a brief overlap or misfiring between the brain’s memory recognition and recall systems. This can cause the brain to mistakenly interpret a new experience as a familiar one, even though it is actually novel.

Can déjà vu be predicted or controlled?

Currently, déjà vu cannot be reliably predicted or controlled. It tends to occur spontaneously and unpredictably. Research continues to explore the neural mechanisms behind it, but no methods exist to intentionally induce or prevent déjà vu experiences.