Paleomagnetism, the study of the Earth’s magnetic field in the geological past, offers a profound lens through which scientists can unravel the intricate tapestry of our planet’s deep history. By analyzing the fossilized magnetic signatures preserved within rocks, researchers gain invaluable insights into geomagnetic reversals, plate tectonics, and even the evolution of life itself. This field, often operating at the intersection of geology and geophysics, provides a unique perspective on processes that have shaped Earth over billions of years.

The Earth’s magnetic field, generated by the convective motion of molten iron in the outer core, has not remained static throughout geological time. Its strength, polarity, and morphology have undergone significant changes, leaving indelible imprints in magnetizable minerals. When igneous rocks cool below their Curie temperature, or when sedimentary particles settle and align with the ambient field, they become faithful recorders of the Earth’s magnetic orientation at that specific time. You can learn more about the earth’s magnetic field and its effects on our planet.

Thermoremanent Magnetization

Igneous rocks, formed from the cooling and solidification of molten magma or lava, are powerful archives of ancient magnetic fields. As these molten materials cool, iron-bearing mineral grains within them, such as magnetite and hematite, align themselves with the Earth’s magnetic field. Upon further cooling below their Curie temperature – a critical point at which they permanently retain their magnetic properties – these minerals essentially “lock in” the direction and intensity of the geomagnetic field. This process, known as thermoremanent magnetization (TRM), provides a robust and often remarkably stable record of past magnetic conditions. The reliability of TRM makes igneous rocks, particularly basalts and intrusive bodies, prime candidates for paleomagnetic studies.

Detrital Remanent Magnetization

Sedimentary rocks, formed from the accumulation and cementation of sediments, also capture paleomagnetic information, albeit through a different mechanism. As fine-grained magnetic particles (like silts and clays containing magnetic minerals) settle in water, they tend to orient themselves parallel to the Earth’s magnetic field before being buried and lithified. This process is called detrital remanent magnetization (DRM). While DRM can be susceptible to post-depositional disturbances, careful selection of suitable sedimentary sequences and meticulous laboratory techniques can yield valuable paleomagnetic data. Understanding the depositional environment is crucial for interpreting DRM, as factors such as current strength and sediment source can influence the accuracy of the magnetic record.

Chemical Remanent Magnetization

Another form of remanence, chemical remanent magnetization (CRM), arises when new magnetic minerals grow or pre-existing ones undergo chemical alteration in the presence of an ambient magnetic field. This can occur during weathering, diagenesis, or hydrothermal alteration. For instance, the formation of secondary magnetite during burial diagenesis can acquire a CRM that reflects the magnetic field present at the time of mineral growth. CRM can be complex to interpret, as it often overprints earlier magnetic signals, but it can also provide crucial information about specific geological events and the timing of diagenetic processes. Researchers differentiate CRM from TRM and DRM through various demagnetization experiments and petrographic analyses.

Deep time paleomagnetic records provide invaluable insights into the Earth’s geological history, revealing information about past magnetic field reversals and continental drift. For those interested in exploring this topic further, a related article can be found at Freaky Science, which delves into the implications of paleomagnetic studies on our understanding of Earth’s climate and tectonic activities over millions of years. This resource offers a comprehensive overview that complements the findings from deep time paleomagnetic research.

Unraveling Plate Tectonics and Continental Drift

One of paleomagnetism’s most profound contributions has been its role in solidifying the theory of plate tectonics. The concept of continental drift, initially proposed by Alfred Wegener, gained widespread acceptance largely due to paleomagnetic evidence.

Apparent Polar Wander Paths

By measuring the paleomagnetic directions in rocks of varying ages from a single continent, scientists can reconstruct the ancient positions of the magnetic poles relative to that continent. When these pole positions are plotted chronologically, they form an “apparent polar wander path” (APWP). Crucially, APWPs from different continents do not coincide, unless the continents are brought together to their ancient, pre-drift configurations. This discrepancy provided compelling evidence that the continents themselves had moved, rather than the Earth’s magnetic poles, thus confirming the reality of continental drift. The APWP for North America, for instance, exhibits a distinct trajectory that differs significantly from those observed in Europe or Africa, demonstrating their independent movements over geological time.

Seafloor Spreading and Magnetic Stripes

The discovery of magnetic stripes on the ocean floor provided a direct and elegant confirmation of seafloor spreading, a cornerstone of plate tectonics. Mid-ocean ridges, where new oceanic crust is generated, act as natural tape recorders of the Earth’s magnetic field. As magma erupts and solidifies at the ridge crest, it records the prevailing magnetic polarity. As new crust is generated and spreads away from the ridge, it preserves a symmetrical pattern of alternating normal and reversed magnetic polarity “stripes” parallel to the ridge axis. These stripes mirror the chronological sequence of geomagnetic reversals, allowing scientists to date the ocean floor and measure the rates of seafloor spreading with remarkable precision. This discovery was a pivotal moment in Earth sciences, transforming fragmented observations into a coherent, dynamic model of Earth’s surface.

Reconstructing Ancient Geometries

Beyond simply proving plate tectonics, paleomagnetism enables detailed reconstructions of past continental configurations. By analyzing paleomagnetic data from rocks of similar age across different continents, researchers can determine their relative positions and orientations at various points in geological history. This has been instrumental in mapping the assembly and breakup of supercontinents like Pangea, Rodinia, and Columbia, providing a grand narrative of Earth’s evolving geography. These reconstructions are vital for understanding ancient climates, biogeography, and the distribution of mineral resources. The precision of these reconstructions often improves with the availability of more robust paleomagnetic datasets from well-dated rocks.

The Dance of Geomagnetic Reversals

The Earth’s magnetic field is a dynamic entity, and one of its most enigmatic behaviors is the phenomenon of geomagnetic reversals – instances where the north and south magnetic poles swap positions. These reversals are irregularly spaced in time and can occur relatively rapidly on a geological timescale, often over thousands of years.

The Geomagnetic Polarity Timescale

Through meticulous paleomagnetic studies of continuous stratigraphic sequences, particularly from ocean floor magnetic anomalies and land-based volcanic and sedimentary successions, scientists have constructed the Geomagnetic Polarity Timescale (GPTS). This incredibly detailed chronology charts the history of magnetic reversals over hundreds of millions of years, demarcating periods of “normal” polarity (similar to today’s field) from “reversed” polarity. The GPTS serves as a fundamental dating tool for correlating geological events worldwide, akin to a global geological calendar. Each polarity interval, or chron, is assigned a name, and shorter reversal events within chrons are called subchrons.

Understanding Reversal Mechanisms

While the existence of reversals is undeniable, the precise mechanisms driving them remain an active area of research. Theories often involve the complex interplay of fluid dynamics within the Earth’s outer core. During a reversal, the magnetic field visibly weakens, and its configuration becomes more complex, often exhibiting multiple poles or a non-dipolar geometry. This weakening phase can last for several thousand years, followed by a relatively rapid flip to the new polarity. Studying the transitional field during reversals offers critical insights into the dynamo processes operating within the Earth’s core. Paleomagnetic data from specific stratigraphic horizons that record a reversal event provide snapshots of the Earth’s magnetic behavior during these tumultuous periods.

Environmental Implications of Reversals

The potential environmental and biological impacts of geomagnetic reversals are subjects of ongoing debate. During a reversal, the Earth’s magnetic field weakens considerably, leading to a significant reduction in its protective shielding effect against cosmic radiation. This could theoretically expose the Earth’s surface and atmosphere to increased fluxes of high-energy particles, potentially impacting climate, atmospheric chemistry, and even biological systems. While direct evidence of large-scale extinctions directly linked to reversals is scarce, some studies suggest correlations between extended periods of weakened field and environmental stressors. The possible effects on satellite technology and power grids in a future reversal scenario also garner significant interest.

Probing the Intensity of the Ancient Field

Beyond direction and polarity, paleomagnetism also endeavors to reconstruct the intensity of the Earth’s magnetic field throughout geological time. This parameter, often referred to as paleointensity, provides crucial information about the vigor of the geodynamo.

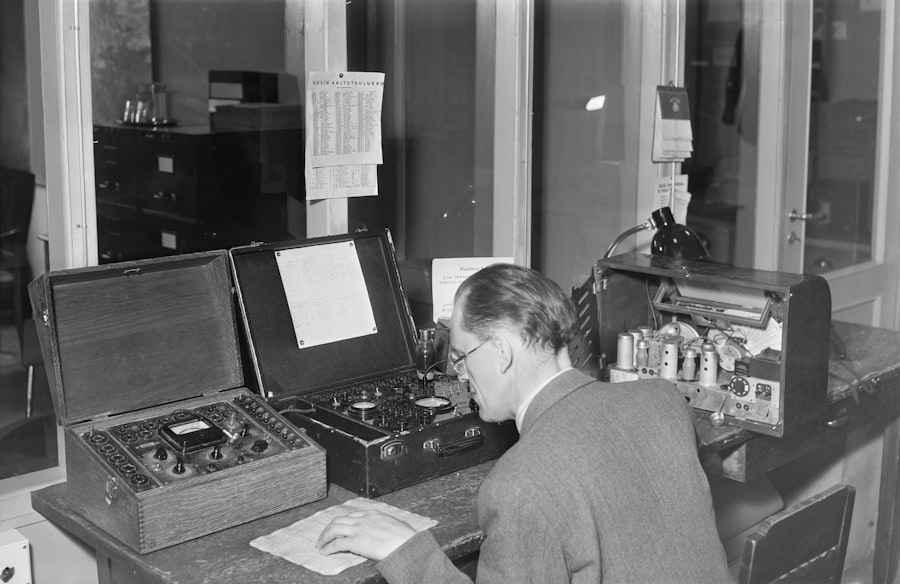

The Thellier-Thellier Method

The pioneering work of Émile Thellier and Odette Thellier formed the basis for the most widely used paleointensity technique, the Thellier-Thellier method. This laboratory-intensive procedure involves systematically heating and cooling rock samples in a controlled magnetic environment, allowing researchers to compare the lost natural remanent magnetization (NRM) with the gained laboratory-induced TRM. By carefully analyzing the relationship between these two components, an estimate of the ancient field intensity can be obtained. The reliability of Thellier-Thellier experiments hinges on several stringent criteria, including the absence of significant alteration during heating and the presence of fine, single-domain magnetic grains.

Long-Term Paleointensity Variations

Paleointensity studies reveal that the Earth’s magnetic field strength has fluctuated significantly over geological timescales. Periods of strong field intensity are punctuated by intervals of weaker field, often correlating with geomagnetic reversals. The “superchron” periods, such as the Cretaceous Normal Superchron (CNS), an extended interval of stable normal polarity, are also characterized by relatively strong and stable field intensities. Understanding these long-term variations in paleointensity helps to constrain models of the geodynamo and provides insights into the evolution of Earth’s internal processes. The study of paleointensity is a challenging but rewarding endeavor, requiring careful sample selection and rigorous experimental control.

Correlating with Core Dynamics

Variations in paleointensity are intimately linked to the dynamics of the Earth’s outer core. A stronger magnetic field often implies more vigorous convection and energy transfer within the liquid iron core, while a weaker field could indicate less efficient dynamo action. Paleointensity data, therefore, act as a remote sensor of core behavior over billions of years. By combining paleointensity records with geochemical and seismic data, Earth scientists build a more holistic picture of the planet’s deep interior and its evolution. The challenge lies in accurately extracting these ancient intensity signals from often complex rock magnetic archives.

Deep time paleomagnetic records provide crucial insights into the Earth’s geological history, revealing how the planet’s magnetic field has changed over millions of years. These records can help scientists understand past climate conditions and tectonic movements. For a deeper exploration of the implications of paleomagnetism on our understanding of Earth’s history, you can read a related article that discusses these fascinating connections in detail. Check it out here.

Paleomagnetism and the Evolution of Life

| Metric | Description | Typical Range/Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Magnetic Polarity Chron | Intervals of normal or reversed geomagnetic polarity | Thousands to millions of years | Used for dating and correlating sedimentary and volcanic sequences |

| Virtual Geomagnetic Pole (VGP) Latitude | Latitude of the inferred geomagnetic pole from rock samples | -90° to +90° | Indicates past positions of the geomagnetic pole and plate movements |

| Inclination | Angle of magnetic field vector relative to the horizontal plane | -90° to +90° | Used to estimate paleolatitude of rock formation |

| Declination | Angle between magnetic north and geographic north | 0° to 360° | Shows the direction of the ancient magnetic field |

| Remanent Magnetization Intensity | Strength of the preserved magnetic signal in rocks | Varies widely, typically 10^-6 to 10^-2 A/m | Indicates the quality and reliability of paleomagnetic data |

| Age Range | Time span covered by paleomagnetic records | Millions to billions of years (e.g., Precambrian to present) | Provides insights into Earth’s magnetic field history and tectonics |

| Reversal Frequency | Number of geomagnetic reversals per million years | 0 to ~10 reversals per million years | Reflects changes in geodynamo behavior over geological time |

The Earth’s magnetic field is a fundamental environmental parameter, and its history likely played a role in the trajectory of life on Earth. Paleomagnetism offers tantalizing clues about this intricate relationship.

Shielding from Cosmic Radiation

The geomagnetic field acts as a protective shield, deflecting harmful cosmic rays and energetic particles from the sun away from Earth’s surface. A strong magnetic field is thought to be crucial for maintaining a stable atmosphere and for protecting exposed life forms from DNA-damaging radiation. Periods of significantly weakened magnetic field, particularly during reversals or extended intervals of low paleointensity, could potentially have subjected life to increased mutational rates and environmental stress. While direct cause-and-effect links are difficult to establish, the geological record provides a framework for exploring these hypotheses.

Links to Biodiversity and Mass Extinctions

Some researchers have posited correlations between geomagnetic reversal frequency and periods of increased biodiversity or even mass extinction events. For instance, the timing of certain extinction events has been speculatively linked to prolonged periods of reversal or weakened field. However, establishing causality is complex, as many other environmental factors (e.g., volcanism, climate change, asteroid impacts) also influence these biological transitions. Paleomagnetic data provide critical contextual information for these broader geobiological investigations. Future research might explore more nuanced connections between changes in the geomagnetic field and the selective pressures experienced by diverse life forms throughout Earth’s history.

Guiding Biogeographic Studies

Paleomagnetism’s ability to reconstruct ancient continental configurations has been invaluable for biogeographic studies. By understanding where continents were located at different times, researchers can trace the dispersal and vicariance of species, explain patterns of biodiversity, and understand the evolution of ecosystems in a spatially and temporally accurate framework. For example, paleomagnetic reconstructions clarify the geographic isolation of Australia and Antarctica, explaining their unique evolutionary trajectories. The magnetic record, therefore, serves as a crucial navigational chart for understanding the grand journey of life across the planet’s surface.

Through the meticulous study of deep-time paleomagnetic records, scientists continue to unlock fundamental secrets about Earth’s dynamic interior, its ever-shifting surface, and the intertwined history of its magnetic field and the life it has nurtured. This field, a bridge between the unseen forces within our planet and the tangible records in its rocks, consistently reshapes our understanding of Earth’s remarkable journey through cosmic time.

WATCH THIS! 🌍 EARTH’S MAGNETIC FIELD IS WEAKENING

FAQs

What is deep time in the context of paleomagnetic records?

Deep time refers to the vast time scale over which Earth’s geological and magnetic history is studied, often spanning millions to billions of years. In paleomagnetism, it involves analyzing ancient magnetic records preserved in rocks to understand Earth’s magnetic field changes over these extensive periods.

What are paleomagnetic records?

Paleomagnetic records are the remnant magnetization preserved in rocks, sediments, or archaeological materials that record the Earth’s past magnetic field direction and intensity. These records help scientists reconstruct the history of Earth’s magnetic field and plate tectonic movements.

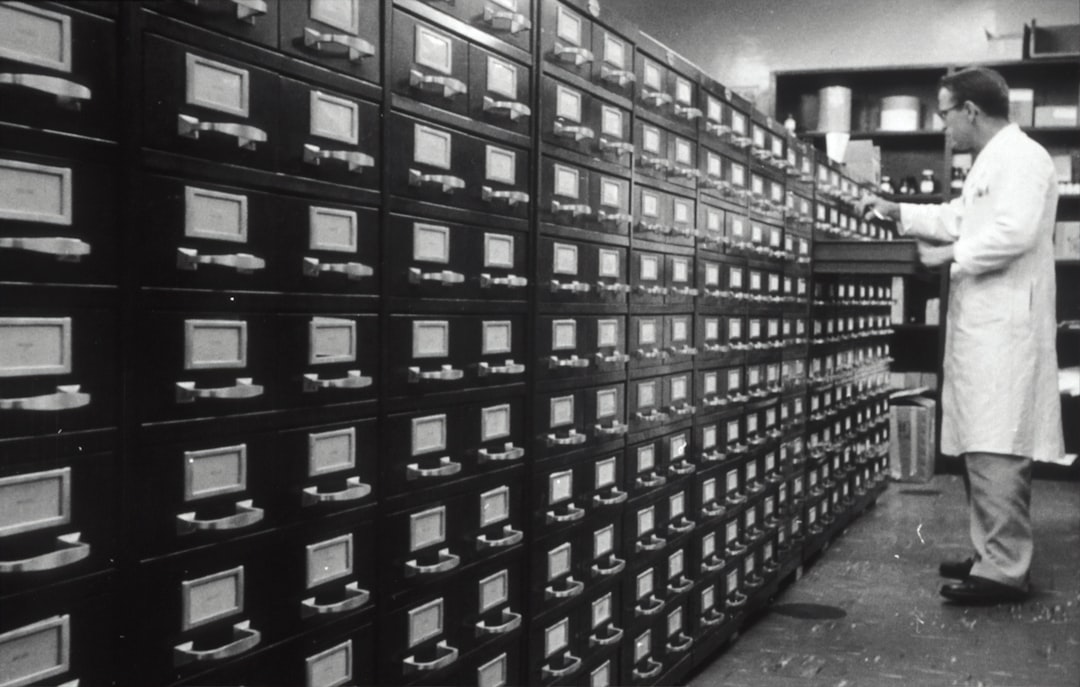

How are paleomagnetic records obtained?

Paleomagnetic records are obtained by collecting rock or sediment samples and measuring their natural remanent magnetization in a laboratory. Techniques include thermal or alternating field demagnetization to isolate the primary magnetic signal from secondary overprints.

Why are paleomagnetic records important for understanding Earth’s history?

Paleomagnetic records provide insights into the past behavior of Earth’s magnetic field, including polarity reversals, secular variation, and geomagnetic excursions. They also help reconstruct past plate movements, continental drift, and the timing of geological events.

What is magnetic polarity reversal?

Magnetic polarity reversal is a phenomenon where Earth’s magnetic field flips, switching the positions of magnetic north and south poles. These reversals are recorded in rocks and serve as time markers in the geological record.

How do paleomagnetic records contribute to plate tectonics studies?

By analyzing the orientation and age of magnetic minerals in rocks, paleomagnetic records allow scientists to track the historical movement and rotation of tectonic plates, helping to reconstruct past continental configurations.

What challenges are associated with interpreting deep time paleomagnetic records?

Challenges include alteration or overprinting of magnetic signals by later geological processes, dating uncertainties, and distinguishing primary magnetization from secondary effects. Accurate interpretation requires careful sampling, laboratory analysis, and correlation with other geological data.

Can paleomagnetic records be used to date rocks?

Yes, paleomagnetic data can be correlated with the geomagnetic polarity time scale (GPTS) to provide age constraints for rock formations, especially when combined with radiometric dating methods.

What types of rocks are most commonly used for paleomagnetic studies?

Igneous rocks, such as basalt and lava flows, are commonly used because they acquire a stable magnetic signature upon cooling. Sedimentary rocks can also preserve paleomagnetic information, though their signals may be more complex to interpret.

How far back in time can paleomagnetic records be traced?

Paleomagnetic records can extend back over billions of years, with some of the oldest reliable records dating to the Archean Eon, around 3.5 billion years ago, providing valuable information about early Earth conditions.